Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

The Queene sendeth her Consort to

Kitania on an urgent errand.

On a cold and blustery day at the hind end of winter, it passed that the Earl of Castor found himself walking alongside Buttons of Soriana, a discovery none to the Earl’s liking, being cognizant of his own graceful appearance and patrician bearing, of belonging to an house of the noblest among beavers, of having many illustrious Earls of Castor as his forefathers and proceeding from a lineage into which not a thimble of muskrat blood had been deposited in nine hundred years, whereas of Buttons, despite his wearing velvet breeches, the Earl knew there was nothing to know, not even the name of the alley where he had been injected into the world. With this alley-cat the Earl was now forced to stroll some distance along the shoreline of the lake whilst making pleasantries. They had to raise their voices for the great din that now came from the rat city almost without cessation.

‘What do you make of this racket, my Lord?’ enquired Buttons. ‘And the great fires the rats have set in their city? In the day there be heaps of smoke, that it is a wonder the vermin have not already suffocated. All night there be a ruddy glow and eke at times great vaults of flame shooting into the sky.’

‘Thir, I am thcarthe the one to thatithfy your curiothity,’ replied the Earl.

‘First, I thought they had built a great oven for brick-baking,’ pursued Buttons. He waited for the Earl to respond. At length the beaver said, ‘Then, there be your anthwer, tho far ath I can thay.’

‘But, my Lord, wherefore this madness to make bricks suddenly?’

Irritated, the Earl replied crisply: ‘I know not wherefore. I am no rat.’

‘I think it may be noise and fire, and no more, to unloin our troops. Indeed, among our ranks there now be dark hints of some fell beast the rodents have lured up from underground, or a new one they have engendered with noisome arts.’

‘No doubt, that there be your anthwer.’

‘A dragon, then, or a basilisk?’

The Earl gave a little shiver, as if to shake off his impatience. ‘No! An artifithe to make of you thcaredy catth.’

‘That be an astute conjecture, my Lord Earl. For, General Mittens reports five deserters caught the other night. A great show was made of their tortures. Their heads now ornament the entrance to the camp. It would be much more effective for our moral, however, if it were proved beyond doubt to be but stagecraft.’

Quod the Earl: ‘If the fowl of the air despithed not catth, thir, thou might athk them what they thee.’

‘Or that cats but had wings, my Lord. By the by, General Mittens doth not share this view of the matter. Thinketh he there be more to it and hath hazarded that you know something about it, whenas didst counsel our Queen to extend the blockade through another winter.’

‘General Mittenth hath alwayth thpoken motht injuriouthy of my folk. I know not why he hateth uth.’

‘Nor do I, my Lord Earl. Yet, there it be. He believeth beavers to be two-faced. Even you, my Lord, he thinketh have been proffering services to both sides.’

‘I would thtrike the one who thaid that to my fathe,’ said the Earl. ‘I have been nothing but a faithful friend to her Majethty.’

‘Of course, my Lord. Forgive me, but I am reporting only what others say.’

They strolled a little further on the strand, until the Earl spoke again. ‘Ath to the doingth of other beaverth, I cannot anthwer for them. We are a loothe confederathy of claneth, with no thovereign. We dethire enmity of no one. We hate taking thideth in the dithagreementth between our friendth. We are not a warlike folk. We are traderth, merchantth, builderth. I wath contracted by your Queen, and I fulfilled my contract.’

‘Then I take it you have had no part in and have no knowledge of the breaking of the embargo imposed upon Ratona?’

‘I will not anthew a quethtion I conthider intholent, thir. I think it better we not dithcourthe on thith matter further. Now, pray, excuthe me. I mutht take thome retht, for, ath you are aware, I leave on the morrow betimeth.’

‘On what business, Lord?’

‘Why, on my own buthinethth, thir. I be a free agent. I do not anthwer to you!’

‘I have charge of this encampment, my Lord Earl, and must know on what errands all come and go.’

‘I thay, thou hast no charge over me! I have a mind to report thine impudenthe to her Majethty and to thee thee flogged and demoted to drill thargeant!’

‘You will have to wait for that pleasure, my Lord, for the Queen is at present in Kitania. She has gone into her confinement.’

The Earl of Castor looked startled. ‘What? The Queen ith in the family way?’

‘She did not tell you? Well, she wanted no one to mark her absence. We trust to hear joyous tidings soon.’

‘Indeed,’ averred the Earl of Castor. ‘Katerina ith to be a mother! I look forward to congrathulating her!’ He walked a little way without speaking, then said: ‘Now I thee a little what you are about! When the cat’th away.’ He chuckled. ‘I thought, thir, her lackey had got a little big for his breegeth. Well, have thy fun while it lathtth. I be an old friend of Her Majethty, and thy thauthiness to me thhall muthh dithplease her.’

‘My Lord, it grieves me to inform you that, had her Majesty her pleasure, your balls would have decorated her Yule tree this past season. It was I who dissuaded her.’

The Earl sneered. ‘I do not believe thee, who art but a gutterthnipe.’

‘You may ask her yourself when next you see her.’

‘So I thhall. I am to go to Kitania to review the damth. Thereafter I thhall go forthwith to the capital and will thee the Queen at the earlietht opportunity.

‘My Lord, there is no longer necessity for you to visit the dams. They are finished, and we are much indebted to beavers for your magnificent work. Indeed, if you did go, I think you would find the dams are occupied by cats. I have already given orders to, well, to relieve your folk of their duties.’

The Earl was growing increasingly perturbed, but he attempted to bluff with a disdainful laugh. ‘That wert a foolithh thing to do! Catth have no thkill to operate the gateth.’

‘True, my Lord, we are not clever with machinery. But we will know how to burn the dams when the time comes, and that will serve the purpose, I think.’

The Earl looked crestfallen, either because his excuse for leaving the camp had been defeated, or by the thought of the ruination of beautiful beaver-work. Sullenly he said: ‘I thee thou meaneth to keep me thy captive.’

‘Far from it, my Lord Earl. You remain Her Majesty’s honoured guest and have complete freedom to go whither you will within this area of our occupation of Ratona. I only worry for your health, my Lord, if you be proved to have been a rat all along.’

The Earl of Castor scowled. ‘Thou art a proper bathtard. I intend thith very night to write a letter to Her Majathty complaining of thy knavery. I chargthe thee, on pain of thy Queen’th wrath, with itth delivery forthwith.’

Buttons bowed his head in submission. ‘My Lord, I shall see she gets it with all dispatch. What’s more, I think I can vouch that you will have an answer. For, know you that I have the honour not only of being the Queen’s lackey, but she has bestowed on me other favours also. As you know now of Her Majesty’s expectations, perhaps you will congratulate me, my Lord, for I am to be a father.’

Now, when the kittens were born, Katerina doted on them a-while, then gave them over to the care of her spinster cousin, Miss Paws, that she might depart again for Ratland and give her full regard to the military campaign. Buttons met her at the frontier. She marked at once disease in his face and asked, ‘What tidings dost bring me?’

‘You must see with your own eyes what cannot be expressed in words, my Queen,’ he said, deferential as always; howbeit now her spouse and eke master, yet he remained her faithfullest subject.

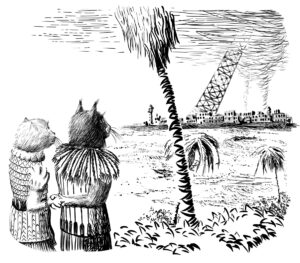

When they were in vicinity of the lake, without delay, Buttons led her to a prominence. They looked across to the rat city and there saw the Queen on legs arched so vastly they spanned nearly the whole of the city a framework. Of no earthly stone could this almighty rib-cage be built, nor brick, nor timber. As it rose its storeys converged as if aiming on some point among the planets. Its members crawled with life. Rats like to numberless maggots laboured over it, like fleas assembling the skeleton of an elephant. As the cats with hanging jaws watched, slaved to their fascination, not one, but several ribs at once, from different sections of the city, were hoisted aloft, rats balanced on the beams as they ascended, clinging to the ropes.

‘Not day by day, but hour to hour and eke minute to minute it rises, Ma’am,’ said Buttons grimly. ‘Night and day do they labour, under the burning heat of the midday sun, under the lamps of the night stars, they labour like ants as needing never to sleep, never to eat.’

In a chill voice the Queen said, ‘ ‘Tis the sorcerer that buildeth this, this maze of black bones. To what end? A ladder to climb and defy heaven?’

‘Yet he be leagues distant. Can his power reach so far?’ asked Buttons.

The Queen spoke not of her true suspicions, saying only, ‘The Rat somehow harnesses his sorcery to his purpose. Fly, Buttons,’ quod she, ‘like the wind, fly to High House. Fly as thou wouldst over fields of scorching coals, fly as if thy tail burned with fire and thou wert its comet, to High House. Find the Architect, and when thou findest him, slay him instantaneously. Slice off his head and bring it me that I may know his infernal power be dead and can do me no more harm.’

Buttons bowed low. ‘Your will shall be done, my Queen.’ So he sprang away.

She remained watching. It was true what Buttons said, for in the little lapse she had stood there, yet another storey of the stupendous structure had coalesced. She startled when to the infernal orchestra of noise coming from the city was joined a great hissing, as of a communion of all the world’s snakes, and the rodent city abruptly belched up a cloud of steam. With a terrible foreboding in her heart, she solemnly vowed, ‘Findeth he the Architect still fastened in High House and I plight thee, most fell of demons, my youngest she-nursling thy couchmate.’

Buttons hastened with all speed back to Kitania, arriving near midnight, his coming awakening all in the royal house. The household, expecting to hear tidings of some outcome in the siege, were disappointed. Buttons would speak only to the Steward, an elderly cat that was Her Majesty’s most trusted retainer. Ere the sun’s rising, the Queen’s Consort and her Steward were flown, the former having slept barely an hour. Next day in Kitania there was much talk over the matter of the Consort’s haste, but little agreement over its reason.

The gates, inner and outer, of Hill House, swung open to admit the Consort and Steward. The guards were astonished and half-alarmed at their urgency. The visitors hurried across the forecourt. Buttons sprang up the wooden steps and pounded the hammer on the oaken door of the donjon, the elder Steward slower in reaching the landing. A head poked out the window above and peered down.

‘Open!’ rasped the Steward. ‘In the name of the Queen!’

The head withdrew. The door remained closed. Again Buttons beat on it and without waiting for answer this time, turned and ordered some of his cats to hurry and gather fuel. ‘Is there another way in?’ he asked the Steward.

‘Certainly, there is the secret way,’ answered the Steward, ‘but it is no less secured. It will take an age to burn down this door!’

‘But less than that to smoke ‘em out,’ replied Buttons. ‘Whether we get in or they come out both answer to the purpose. Ha! What’s this? Arms!’ All drew blades, for there had come from behind the door the muffled sound of bolts slid back. On oiled hinges the door noiselessly swung ajar. In the gap stood a scared servant, but not the one who had stuck his head out the window.

‘Good evening, my Lord.’

‘Let us pass!’ Buttons did not wait for the servant to widen the opening, but gave the door a violent shove, the servant jumping back to avoid being brained by it. The cats entered all, swords at the ready, prepared for ambush. So far, however, the only inhabitant in view was the frightened servant wearing an ingratiating smile.

‘Her Majesty’s Consort hath come to see the Architect,’ said the Steward.

The servant bowed. ‘Of course. I shall see whether he be disposed, Excellency.’

‘We care not whether he be disposed or no, for our business is urgent,’ quod Buttons, ‘So be quicker in announcing us than wast answering the door!’

‘Immediately, Your Highness,’ gasped the servant, and fled.

He did not return. The Consort blasphemed and bade his cats make thorough search of the donjon, breaking down any door barring their passage. Everyone no matter of sex or rank was to be arrested. Meanwhile he had summoned the guards on the wall.

‘What hath passed here?’

‘Nothing, Your Lordship,’ answered their Captain in some surprise. ‘All hath been uneventful, and indeed, there have been no visitors since Your Lordship’s to-day.’

‘Surely there were deliveries?’ insisted the Steward.

‘Naturally, begging your pardon Your Worship, but they were received at the gate, as was strictly ordered. Nothing but food and supplies have passed through. As were our instructions,’ the Captain emphasized, worriedly, for he could see in the eyes of the Consort and Steward that something was amiss.

‘Your Honour, we’ve found not a soul,’ reported one of Button’s own cats, dashing into the room.

‘No one?’

‘Not apart from some half-starved rats chained in the cellar, who I am not positively certain are yet tenants of this world.’

‘But the servant that was here?’

‘Not to be found, Your Honour.’

‘They’ve all fled,’ said the Steward, sounding incredulous. ‘That servant last of all, by the secret door.’

‘What, fled just now, upon our arrival?’ asked Buttons. He looked interrogatively at the Captain of the guard. The Captain, looking nervous, said:

‘Your Honour, I vow, on the grave of my mam, and my cats will vow withal on the graves of their mams, or, or, if their mams still live, on the—’

‘The divil!’ thundered Buttons. ‘Was a ninny put in charge of this jail? Spit it out!’

‘I do swear, this donjon hath been occupied the whole time. There was always someone to answer at the door.’

Then one of Buttons own cats said, ‘Your Honour, that may well be true, yet there is every sign that the Architect’s private rooms have not been occupied since—’ he shook his head in doubt ‘—for some time, Your Honour. I think he may have escaped, and they were too afraid to report it.’

‘Escape is impossible,’ insisted the Captain.

‘Be he not a magician?’ someone suggested.

The other cats considered this.

‘Perhaps he died,’ proposed another cat. ‘Perhaps they buried him. Under the paving stones.’

The old Steward shook his head regretfully. ‘This is not going to please Her Majesty.’

Buttons gave the Steward an annoyed look. Then he said, ‘Show me those rats you found. They must know something.’

So, the Consort was led to the cellar. All of Brussel’s rat slaves, save Nayel, were chained inside a low-vaulted cell.

‘Who here,’ said Buttons, voice ringing as he addressed his captured audience, ‘can tell me what betided the Queen’s Architect?’

The rats, dead and alive, were equally unresponsive. With heads sunk on their chests, they had their eyes rolled up, staring with the glazed, sightless eyes of the deceased and near-deceased.

‘Speak, one of you,’ quod Buttons. ‘He that answereth first shall be granted his life.’

Then, unexpectedly one of the prisoners, perhaps more deranged than the others from fever or thirst, wheezed. It was perhaps laughter, but it sounded like a fireplace bellows. He winced and grimaced with the pain that voiceless gasp caused his sides. The Consort pointed at him. ‘That one,’ he ordered. ‘Let it down. Give it a spoon of watered gruel for start. When it be restored a little in health we’ll have the truth from it.’

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.