Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

Hith Exthelenthy the Earl of Cathtor

tendereth a propothal.

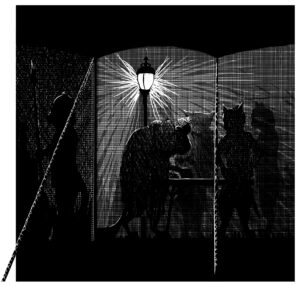

With the Architect safely clapped up in High House for the remains of eternity, the Queen led her army to besiege the rat city. First, they captured all the surrounding settlements. They set up garrisons on all waterways, cutting supply routes to the city. What rats they captured were trussed up and couriered to Kitania for the Cat Goddess’s sport.

When Katerina’s army had secured the perimeter of the lake, hundreds more cats arrived, representing every rank and trade of Kitania, until a thriving town had been established to support the army: cooks, barkeepers, whores, tailers, laundresses, lackeys, smiths, dentists, bone-setters, physicians, astrologers, harlots, clowns, grifters and swindlers, tanners, innkeepers and floozies, and midwives, lawyers and undertakers. Even the Chief Priest and other clergy moved to the encampment to oversee religious services. The Earl of Castor and his retinue also moved into this military burb.

Queen Katerina, High Priestess and most devout observer of her religion, most desirous of martial success, made nightly offerings and prayers to an icon of the Cat Goddess, carved from basalt, installed in a small shrine in her pavilion. One evening after these devotions, she held parley with Buttons of Soriana, General Mittens, a venerable warrior well-seasoned from many campaigns, and that ornament of beaver peerage, the fragrant Earl of Castor.

Buttons said, ‘Ma’am, so low now hath sunk the lake that an archipelago of small islands maketh stepping stones by which we have approached within bowshot of the city walls. This be owing to the genious and labours of our allies the beavers.’

The Earl accepted the praise with a complacent smirk, disceetly screened by a little temple he made of his earth-claws.

‘We are happy to hear this, Lord Castor,’ quod the Queen. ‘We can assure ourselves and eke delight in the gnawing anxiety suffered already by the Chief Rat. Well scraped of skin shall be his knees in pathetic grovelling before his weenie god.’

‘It be but the overture of his tribulations, Majesty,’ said Buttons. ‘To-day, General Mittens ordered our first strike ‘gainst the city.’

‘With what result, General?’

‘No doubt increasing the enemy’s disease, Ma’am.’ answered the General, dipping his head, ‘as we intended. Indeed, we want no more than to harass the rats at present. In such wise we wear them thin. Well taut with fear they’ll be once they behold our war engines deployed on the field. We want them crumbled in heart afore we bash their walls.’

‘They may surrender before that,’ quod the Queen, a weird glimmer in her eye squirming with relish. ‘Especially when they see their lake parched dry. Come, when shall that be?’

‘None be better to speak to that matter than our noble Earl of Castor,’ said Buttons.

All eyes fell on the beaver.

At a grand gesture of the Earl’s paw, two of his underlings scurried up and unrolled upon the table a parchment. ‘Your Majethty,’ he began, with another august sweep of his arm inviting her to peruse the map. ‘My good thir, may I, indeed?’ By this courtesy he meant that Buttons of Soriana ought to get out of his way so he could stand beside the Queen. ‘I beg pardon, my Lord,’ said Buttons, with a deferential bow stepping back. Quod the Earl of Castor: ‘Your Majethty, beaverth are not wont to wait on Nature. beaverth command her to therve our will, who are her huthband and lord.’

‘Very good, my Lord. Expound, prithee,’ answered the Queen, gazing at the map.

Then the Earl explained that the parchment was a map of the lake and its environs. He showed her how through their earthworks the beavers were marshalling all the remaining water into a single body, to be refreshed by a stream from one the reservoirs in the mountains. This was to provide the water needed for Her Majesty’s army, while denying any to her enemy. Once the channels were completed, all the remaining lake-bed would dry quickly, providing ample approach for any sized force with which the Queen was pleased to assail the city.’

‘Then we have not long to wait at all!’ exclaimed the Queen in a small fit of ecstasy.

‘A fortnight, Your Majethty,’ replied the Earl, shiny with conceit.

‘That’s all well and good,’ said Mittens, in a brusque tone somewhat offensive to the Earl, ‘but we have still to force the turtle from its shell, which shall be divilish hard.’

‘That, of courthe, General, be a nut for your jawth’ cracking,’ quoth the Earl.

‘My Lord Earl,’ said Buttons, stepping up eagerly and placing a finger on the parchment, ‘if beavers be masters of such marvellous earthworks as these, then of what else may they be capable? I am thinking of tunnelling and undermining of the city walls.’

‘Indeed, are you tho thinking, thir?’ returned the beaver stiffly. ‘ ‘Tith uncanny how many featth be accomplithhed in the blink of an eye by the mere thinking them. Why, I mythelf in my fanthy do fly to Bagdad and back whenever I want a changthe of clime!’ Then to the Queen he jibed, ‘I’d give him the honour of pulling down the firtht thtone on top of hith thoughtful crown!’

‘I beg pardon, my Lord,’ said Buttons. ‘I intended not to propose some impossible task, or work beyond beaver ken and skill.’

The Earl of Castor drew himself very erect. ‘thir, I did not intimate thucth work to be beyond our ingenuity. Only that it be a feat laboriouth and perilouth.’

‘It likes me greatly this charming idea,’ said the Queen, ‘of the walls’ falling down and the surprised rats’ tumbling out like bon-bons from a box. Natheless, I do perceive the dangers of such underground work, the which I feel we cannot ask the beavers to incur, when indeed this be a war of cats to fight, beavers having no feud to set right with the rats.’

At this, General Mittens broke in. ‘No keener truth was ever spoken, Ma’am, for there be so little feud between rat and beaver, beaver being, speaking plainly, but bigger rodents, that a wonderful—’

The General’s exposition was interrupted by a resounding crash. All looked and saw that the Cat Goddess was no longer upon her altar, having tumbled to the ground.

‘Dear me, dear me,’ said Buttons. ‘How clumsy I am! I crave your pardon, Ma’am!’

‘What happened?’ asked the astonished Queen.

‘Somehow I lost my balance and fell into the altar.’

The Queen said, ‘Buttons, if canst not avoid lurching into things, pray leave us and rejoin thy cupmates,’ to which the Earl of Castor tittered. Then, when they had got the Goddess restored on her altar, the Queen said: ‘Where were we? Well, I will be surprised if they do not surrender betimes, once they are without water.’

‘They can sink wells, Your Majesty,’ said General Mittens.

‘Wells also run dry when not refreshed, General.’

‘These rats are ingenious and resourceful Ma’am, like unto our friends the beavers, to whom, as I lately mentioned, they are akin.’ Here the General passed a glance at Buttons, who threw back a warning one.

‘The important difference being, General,’ said Buttons, ‘that the beavers have proven to be our true helpmeets.’

‘I grieve the General hath formed an unfavourable prejudith ‘gaintht uth,’ said the Earl, ‘on rather little evidenth.’

The General was about to rejoin, but Buttons stopped him with a paw to his arm and said, ‘The General speaks rightly of the rats’ ingenuity, Ma’am. They have, it doth seem, built catapults. They are base copies of our own machines, doubtless. Which machines to-day were used against us in the field.’

‘Indeed?’ quod the Queen.

‘Indeed, ma’am,’ said the General. ‘And most diabolically fashioned they be, with most divilish aim and range.’

‘But what store of munitions have they?’ asked the Queen ‘Let them take apart their stinking hovels brick by brick to fling at us! What will it avail them in the end, but, besides waterless, being houseless to boot?’

‘We would all have our brains spilt out long before they flung the last brick, ma’am,’ said the General. ‘We cannot advance without shelters of some moveable kind for the troops.’

‘Then we shall build them. Mean-times, draw back your troops, General. This be a waiting game. I am nothing if not patient. I hope we suffered not many casualties in to-day’s exchange?’

‘None whatsoever, Madam,’ answered General Mittens, ‘for ‘twas not munition the vermin volleyed, but filth and rubbish, offal, bones, wormy fruit and rotten vegetables.’

She stared at the General, then laughed. ‘Come! This be what daunteth us, General? They will not drive us off our purpose with such slime as that! I know we felines are sometimes fastidious of our cleanliness, but we cannot be killed with mouldy carrots!’

‘They mean to humiliate and thus to provoke us to impulsive action, which bait we shall of course disdain, Your Majesty,’ said Buttons. ‘Mean-times, they give us important intelligence, inadvertent perhaps. Bones and scummy greens, unappetizing though they be, natheless are edible to the hungry, Madam.’

The Queen shrugged. ‘Even the hungry may turn up their noses at rotten food and chuck it.’

‘But not the starving,’ returned the General. ‘And ‘tis now four months we have blockaded that bastard city.’

‘They might have had enough store of food for four months,’ said the Queen, a little stubbornly.

‘Or far longer,’ said the Earl. ‘For what good be a walled thitadel without thuffithient thtore to outwait the aththailant? You may thtill be thitting on the doorthtep come thpring, waiting to be let in.’

Here, General Mittens snorted with frustration.

‘Your Majethty,’ continued the Earl of Castor, ‘Will you hear our propothal?’

‘Proposal?’ queried the Queen. ‘Speak, by all means speak, My Lord Earl. I am all ears to hear it.’

‘We beaverth read the tree ringth. The winter to come will not be cold, but it will be long and in the mountainth heavy with thnow. Very heavy. You have theen how exthellent well we have built you your damth. Let uth add height to them and thtrengthen them in preparathion for another winter.’

‘Another winter? You mean, carry on this blockade through another year?’ exclaimed the General. ‘Why not three winters, or five? Why not till Hell freeze over? We can go on paying the beavers to build dams until they are high as heaven! This be no more than a coin-collecting scheme!’

‘I take umbrage at that, General,’ retorted the Earl.

‘Prithee, gentlemen,’ said the Queen. ‘Let us not speak harsh words one to the other. Sure, we seek all the same end.’

General Mittens was about to burst out with another barrage of words, but Buttons again stayed him with his arm. ‘Let the Earl of Castor finish his speech.’

‘Not five yearth, not three yearth, not even one year, your Majetyty, but only a few thhort monthth of building and waiting till come the thpring. Then we open the damth.’

‘We open the damth?’ repeated the Queen.

The Earl of Castor nodded. ‘Ekthactly. We open the damth. Two winterth of thtored water will wathh the thity of ratth into the thea like thhit down a thewer.’

Her Grace’s eyes opened wide as having descried at a distance the plains of Elysium. When she had recovered her composure and thought she could speak without sounding giddy, she said, ‘Your proposal much intrigues us, My Lord Earl. Pray, permit us a little while to consider it between ourselves?’

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.