Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

After love-making, war.

To bugle call the city gates swung open and from her mouth Felina disgorged her mighty army. Every bell in the citadel was set a-ringing with gladness for the happy day. Every drum was pounded, every cymbal clashed, every ladle to be found to ring every pot was so employed, and every voice was raised in hoorays till every voice was hoarse. Above the hullabaloo, Katrina stood proud upon her battlement, watching whilst one row of her warriors after another passed beneath and saluted her. Eke was she arrayed for battle, with helm upon her head, her breast clad in armour and jerkin, a spear grasped in her paw. Neither, she had vowed, would she divest herself of her war garb till the Grand Rat on the shoulders of his own rats was borne through her gates and laid upon her altar. Five hours, according to later Rat yore, it took the feline army to march out of Kitania. Ginger at its head with his standard bearer had reached the canyon floor whilst a mile up the city had not emptied herself of warriors, as if a factory turned them out in limitless supply. When once the clamour of the ecstatic city was left behind the windings of the canyon, Ginger drooped. He was knackered. Angrily he fought off his weariness, drew himself erect and bellowed the beginning of a marching song. It was relayed back more rapidly than fire kindles one tree after another until it was taken up by the entire army in one roaring flame. Up it rose, bold and insolent, yet growing a little fainter at every bounce against the stone walls of the canyon, till only a whisper reached the ears of the raptors who, frustrated in their hunt, with minute adjustments to their pinions, broke out of their spirals and set sail for neighbouring, silenter canyons.

Long after the tail of her army had disappeared, Katerina stood on her balcony, insensible to the chill wind, of her own weariness, pensive.

The previous evening, having voided all but Ginger from her Bed-room of State, she had said to him, ‘Good my dear Consort, ‘tis mine own heart I send tomorrow on this perilous errand. I beg thee return it sound and without hurt.’

‘Thou hast my insurance, my Lady Queen,’ returned Ginger, dipping his head. ‘I will not fail thy trust to bring home thine army whole with war booty withal, slaves and victims, and treasure enough to overflow your coffers, and the Great Rat himself upon a salver to furnish the grand finale of our victory parade. Doubt not the doughtiness of me thy Captain, nor of thy warrior braves. So unworried am I of the ease with which we shall crush the Rat’s skull between our teeth that I make thee a compact to submit to one lash of the thong for every cat I lose thee.’

‘Thou hast ever been a braggart, my tom-cat,’ quod the Queen, ‘and over-bold in word and deed.’

‘There is no winning in not wagering, Ma’am.’

Queen Katerina approached him and took her his paws into her own. As she squeezed she deployed the points of her talons so they dug in a little, but winched not he did, as she stared up into his eyes. ‘My fond tom-cat, when I say mine heart, I mean not mine army. I speak of the helpmeet in all my trials and the delight of all my delights. Return that.’

Soberly he said, ‘That, too, I pledge, Ma’am.’

‘Take no unnecessary risks. Do not be foolhardy. Keep thee thine ear and nose pricked for scent or sound that may augur ill. Keep an eye open always for the unexpected menace.’

‘My Lady Queen hath no need to alert her Captain to the perils of war or the vagaries of battle. She knoweth him to be a seasoned warrior and a canny general who never yet hath failed her.’

‘Never yet, Ginger. My heart, I tremble to discover to thee my terrible foreboding, lest its haunting cause thy step to falter. Forsooth, doubt fashions a poor leader.’

‘ ‘Tis poison indeed to bibb, but I be a teetotaller when it comes to all such ranksome liquors, Ma’am. Pure water I drink when I may not guzzle blood, for such wholesome beverages cripple not the spirit nor whither the eggs.’

‘Ginger, heed me. I have tried to banish these perfidious phantoms from my brain, but I cannot put out of mind the celestial visitor. Nought passes but is for well or ill.’

‘True also of butterflies and hornets, my Dame, but to pursue one and evade th’other is to be a kitten dashing in circles. To stride the straight path of success one must keep honour to one’s fore and the scourge of dishonour to one’s rear. Only by this can one’s destiny be reached. This be our ripest opportunity, as their errant god dallies abroad, to erase the foul rodent city from the face of Earth. Henceforth rats will be our livestock to breed to our purpose, to slave for our pleasure or to gorge the maw of our drad Goddess. So, prithee chase these imps from thy brain, my Lady. Do not listen to the old-maid palaver of thy priests, dusty with the dust of their prophesy scrolls, clapped up in their schoolrooms till they jump with womanish fears. Thou beest more mannish than they. Do not surrender to the frailty and timidnous of thy natural sex. Renounce thy sex, Ma’am, to be sovereign of thy nation. Remember that thou alone art Kitania.’

‘To-day, Ginger, I was Kitania. On the morrow I will be Kitania again. But to-night, Ginger? Might not my feminine sex have to-night at least? May I not indulge my womanish sentiments for a space? Whom indeed will Kitania have, if her knight returnest not? No, Kitania must have her knight. He shall not depart from her bosom.’

‘Madam, these words be baffling. Bidest thou I pass to another general this occasion to bring thee glory? Am I to be kept at home like an housecat, petted, cuddled, fed morsels from your table, dressed in bonnets and teased with a ball of twine, whilst abroad thine army wadest to the knee in rodent blood? Knowest not my measure, dame, if this be thy urging, albeit I know thine enow to know thou’dst disdain me if I gave thee let to castrate me thus. ‘Tis no eunuch chose thou to fetch with.’

‘Tis no eunuch I want, Ginger. I chose a rude-mannered tom-cat, boastful, rough, fanged, clawed, cruel, well-pricked and balled. For that I demand of him a surety ere he departest, lest there be no coming back after.’

‘Madam, what surety canst he vouchsafe, save his word already declared?’

‘His felinculus.’ So drew him she from the Bed-room of State into her Privy Bed-chamber.

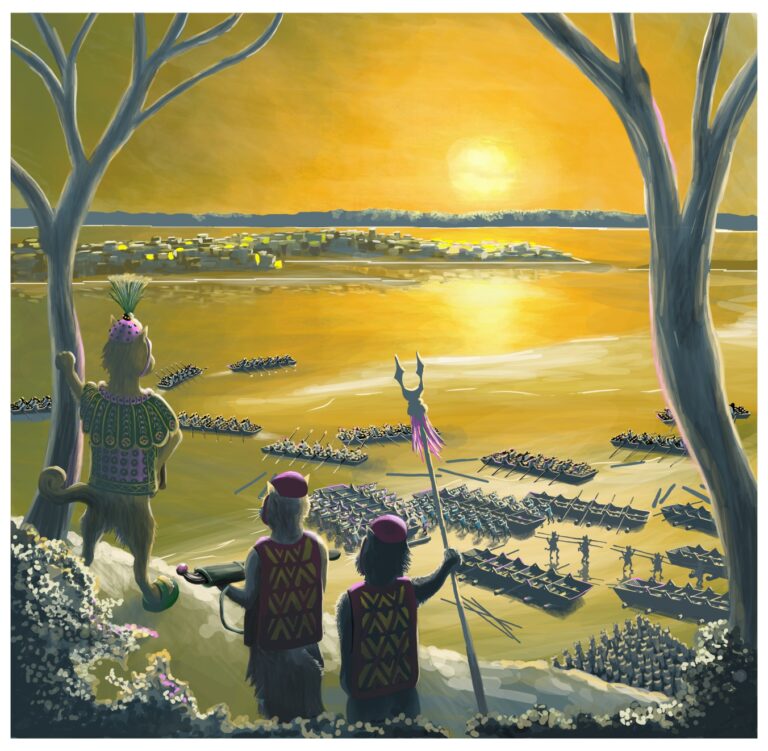

Night-fall when the sapphire stars were a-borning in the vault, from the forest slinked the cats. The thirsty river was reduced to silver strands braiding amongst a toy archipelago of new islets, providing the cats many places to ford, so that the divisions were stretched into a long front. The first cats dipped their toes with loathing into the clammy water and recoiled, till their fellows behind shoved them forward with curses. In such wise the Enemy spilled into the river-bed, swamping it with felines, and boiled up on to the other bank like a surf, a furry flood flowing into Ratona, gliding so rapidly that no alarm could out-speed that tide.

They plashed in the star-decked pool, then dandled on its shadowed bank in long silken grass. No sound disturbed the night save their own murmurings, their soft gasps and the occasional grunt of a bull-frog. Then Nayel grew alert and pricked his sensitive ear. He had heard a distant rumble. He scaled a trunk, limber as a monkey, and disappeared into the foliage. When he came down again, he was trembling with excitement. He whispered into the Architect’s ear that all around them shadows slid through the foliage, feline shapes slinking from limb to limb. Alfred A. Brussel pressed a hand to his mouth to prevent himself from squeaking. ‘But it is still three days until the rising of the Cat’s Teeth,’ he objected in a whisper. ‘Curses, I thought the priest-ridden folk in these parts didn’t evacuate without checking their horoscopes. How extraordinary that they suppressed their superstitions to gain the advantage of a surprise attack.’

‘What shall we do, Master?’

Brussel tried to collect his thoughts, for they were scattering in all directions like roaches caught in the light. The situation none-the-less demanded an immediate response. He flew to a decision, and seizing the ratling’s arm he whispered urgently, ‘Run my boy, fast as a hare, to the city. Be as fleet as those supple young legs of yours can make you and warn them. Tell them that I, Alfred A. Brussel, have seen Katerina’s army.’

‘Yes, Master,’ said Nayel. ‘But what about you?’

Brussel had concluded that it would be imprudent to return to the city until the victor of the battle were known. Far safer was it to be on the outside of the conflict. That would make it possible to present oneself on friendly terms to whomever had won. With luck, the business would be settled by dinner the following evening. So, he said, ‘I will follow, but you must run ahead. I am not the svelte young man I once was and would only slow you down. Now, go!’

Nayel was most reluctant. ‘No, Master, it’s unsafe. And we brought only the one canoe.’

‘Never mind about me, my lad. The welfare of the city is far more important. Go, I say, before I grow impatient.’

‘Very well, Master. I will send back help as soon as I reach the city.’

‘Do that.’ Alfred A. Brussel grew hesitant. He did not release the ratling’s wrist, whilst staring at him intently with one eye as with the other he calculated fiercely on whether there might not be an alternative. ‘Be sure to tell them to light the signal fires.’

‘Yes, Master!’

‘Be sure to tell them to muster the guard!’

’Yes, Master!’

He did not let go of the wrist. ‘Quick now! Tell them to make the gates fast! Prepare the boiling pitch!’

‘Yes, Master!’

‘The life of the city depends on you, my boy. Can you do it, do you think?’

‘I, I think so, Master,’ said Nayel, looking down at his wrist, still prisoned in Brussel’s grasp. He tested whether he might pull it free.

Brussel pulled it tighter. ‘Then for God’s sake, run. Do not neglect to tell them to fill the fire buckets. And above all, protect the women and children! Did I mention the boiling pitch?’

‘Yes, Master!’ Again, Nayel tried to break free, but Brussel pulled him still closer and smacked a hard kiss to his cheek. ‘Dear boy, be careful! Keep to the shadows. Fly on winged feet and be as swift and silent as the hawk’s wing!’

‘Yes, Master!’ Nayel at last broke free and in two leaps was gone.

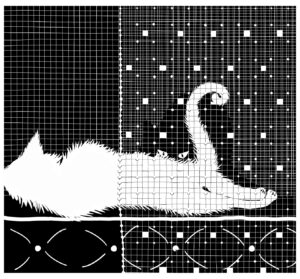

Alfred A. Brussel immediately rued his decision. He felt lonely and afraid. He was far too terrified to budge, not with the trees crawling with cats that would be apt to shoot anything that stirred. He might as well be a sow waddling to its slaughter as try to escape. Proceed as cautiously as he might, his emerald eyes, visionary as they were, could not out-see a cat’s in the dark. So, too cowardly to venture out, and convincing himself it was wiser to wait until day-light, he rolled himself in the mud until all his pale pink skin was camouflaged. He crawled under a shrub to wait out the night. Lying on his side, he stared through a small gap, on guard for any tremble of a leaf, ear pricked for any rustle of a leaf. The stars, spangling in the black water of the pool, silently blinked out of existence. The sky was shuttered. Cloud cover, he thought. That at least will help the boy. Then he caught his breath, for the faint rumble earlier heard by the ratling now repeated, but nearer now so he too heard it. War drums, he thought, incorrectly.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.