Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

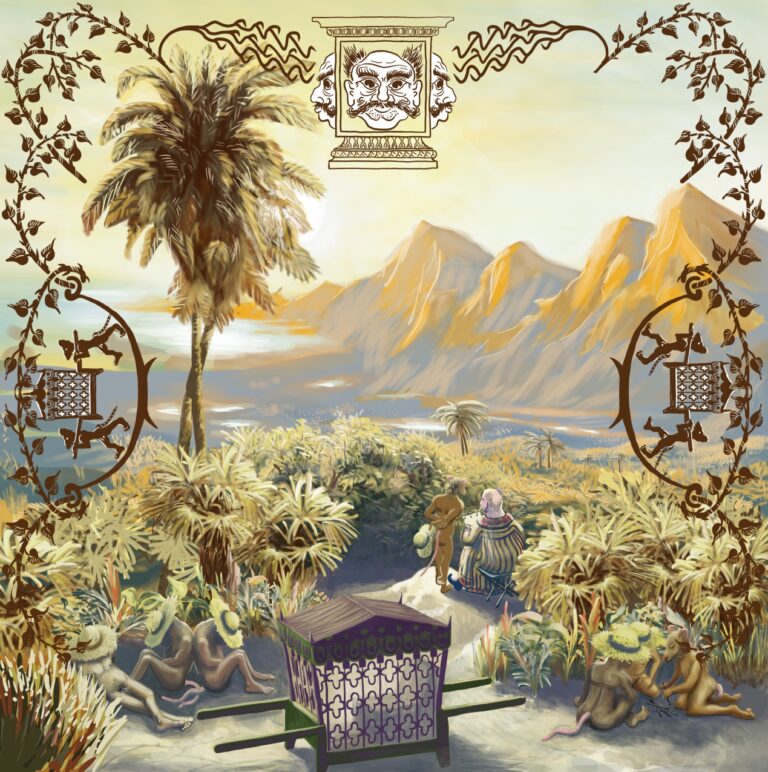

The Architect enjoyeth the beauties and pleasures of

Ratona whilst the King groweth impatient.

As Alfred A. Brussel unpacked his portmanteau, the Steward watched with fascination as one mystifying object after another was brought to light. There were instruments finer than any seen before in Ratona, smooth, polished, with perfectly straight edges. Some had curious ciphers inscribed into them, others had moving parts, or were connected by wires. There were metal pens sharp and as lethal looking as darts, compasses and dividers. There were rolls of vellum. The Steward opened a book and beheld figures that were without doubt grammarie. He closed it with a shudder and picked up the next object that Brussel had taken out. Hinged like a jaw, it snapped shut, to his startlement.

‘My good fellow, please don’t touch,’ said Brussel, giving the Steward’s hand a light slap, which further astounded the Steward, who had not been slapped since a ratling. ‘These implements are more precise than a surgeon’s and irreplaceable in this . . . this . . . this far west of Chicago. If you’d like to be useful, I am a little peckish. Could I trouble you to run down and ask Cook to scramble some eggs and fry a few sausage links? With a mug of something cold, if it can be had.’

The Steward’s face hardened into a mask. He gave a sharp, indignant clap to summon a house-boy. This outsider had the regrettable habit of treating everyone the same, save himself. He lacked appreciation of the many ranks in Ratonian society. The Steward would have liked to inform this outlandish foreigner that his family had proudly served as stewards to the kings of Ratland for the last 3317 years, at last reckoning, whereas a stranger like himself, having no official ancestry, could hardly be said to exist.

The Steward’s dislike of the Architect had, in fact, been immediate.

‘Oh, this won’t do, this won’t do at all,’ Brussel had said the previous day, when the Steward had shown him the quarters he considered appropriate for one of no rank and whose function in the palace was, as far as the Steward could see, unfathomable. The Steward thought that someone whose previous lodging had been a hole with a grate over it should be overjoyed by the Steward’s choice. ‘I want at least three rooms of tolerable size,’ Alfred A. Brussel had specified, unaware of the Steward’s hostility, or, more galling, indifference. ‘One at least must have ample north light. Higher up, preferably, to be well-aired. I am sensitive to odour. I do not ask for luxury, but I must be reasonably comfortable. I’ll want two or three boys to attend to my domestic chores and to be otherwise at hand for my needs, versatile lads well-behaved and obedient.’

True, the Architect had been effusive with gratitude when the Steward had shown him an alternative suite of rooms, but had promptly dulled the lustre of the moment by saying, ‘Now, just a word in your ear about meal-times. I do like to take a little wine at luncheon and dinner. I find a periodical glass of the grape throughout the day salubrious for the constitution. Moderate and regular consumption of red wine is the explanation for the Latins’ living so long. And a masseuse. Bending over a table all day, you have no conception of what it does to the back. Oh, pray don’t fear I’ll be demanding. I promise you I will be as content and easy a house guest as could be wished if the few items on my list are provided. You won’t even know I’m here!’

Three weeks passed and no construction had commenced, but only some bricks and timber had been stock-piled. The King grew impatient.

‘What doth he with his day?’ he asked. He and the Steward were running over household accounts. The Architect had ordered additional furniture for receiving guests in his apartment.

‘He riseth late, my Lord,’ answered the Steward. ‘Well after the sun. After he hath broken fast, he ventureth afield. The purpose of these jaunts, sayeth he, is to commune with Nature, to learn her pattern and to riddle the secrets of her beauty. He contemplateth also the divine plan of creation, so he sayeth. This, sayeth he, is how he findeth inspiration for his own humbler works.’

‘Fripperish verbiage and flim-flam!’ retorted King Othon. ‘I know the purpose of these sallies. All the sneak riddleth is some way of escape!’

‘I ween it not, Your Highness,’ said the Steward. ‘For, he travelleth in a palanquin, alighting only to admire a particular view, or to study a plant. His attendants report that he be remarkably clumsy and short-winded. Furthermore, he seemeth attached to the comforts of Your Highness’s palace, and hath become moreover affectionate towards Aldao, the young rat he sendeth on errands.’

King Othon’s jaw had dropped, but no words dropped out. He had ordered his household to comply with any request of the Architect, never imagining he would take the liberty of ordering a palanquin, a level of status no male except of the royal family enjoyed.

The Steward, hesitated on seeing the King’s bewilderment, but as the King continued to say nothing, the Steward continued. ‘After his mid-day meal, he confineth himself to his quarters. He draweth lines on his sheets of vellum, remarkably slender lines, both straight and curved, with his instruments. These lines form elaborate patterns, my Lord, that are most fascinating.’ The Steward paused, uncomfortable. That had sounded too much like admiration. The truth was, despite his dislike of the Architect, he was intrigued by his drawings. He was nearly disposed to believe that the Architect did have some magic to draw out the secrets of nature. Then, too, there were the startling emeralds that were the Architect’s eyes. The Steward had barely marked them when first he met the Architect, but they made him increasingly uneasy, for they seemed not mere organs of sight, but to have some illuminative power of their own, like those of cats with their uncanny ability to see in the dark. The Lord Etiam had doggedly insisted the Architect was a kind of cat, at which the King had scoffed, but the Steward wondered whether he should mention his own suspicions to His Highness. He continued his account of the Architect’s routine: ‘When the heat of the day abateth, he goeth forth with Aldao to bathe, returning to the palace at nightfall to sup. Most evenings he passeth sociably. I have been surprised at the quantity of lamp oil he consumeth, my Lord, and fear I must order more, lest Your Highness goeth without.’

Running low on candle oil was not what His Highness was worrying about as he half-listened to the Steward. His spies informed him that the war preparations of the cats were complete. Two likely dates for attack had passed already, and now Othon’s astronomers had their sight fixed on the Rising of the Cat’s Tail for Katerina’s choice. If the rains still delayed, the cats would be able to march straight up to the city walls.

Later that day, he spoke his thoughts to his Groom of the Stool. ‘I will issue an ordinance that, saving our warriors, no rat shall eat neither flesh nor eggs until the rain cometh. There shall be no bathing, the penalty to be cutting off of the tail. Half the city’s daily water ration shall be boiled off before the temples as sacrifice. No seed shall be expended. Males and females shall be segregated, not excluding husbands and wives, on opposite banks of the Great Canal. Let penalty for conjugation be emasculation. The people shall be divided into six watches, that prayers be sent up without cessation day and night.’

‘As it pleaseth my Lordship,’ said the Groom of the Steward.

‘It pleaseth him not,’ said the King gloomily. ‘Yet we be in desperate times.’

Alfred A. Brussel was dismayed upon learning of the new strictures, especially against his daily bath. He begged audience with the King, and having made obeisance, said, ‘Your Highness, surely your Steward misunderstood your intentions. He seems to think that palace officials are under the same interdicts as the regular folk.’

‘Even the person of Othon the Eighteenth is under command of the ordinance and may not bathe, Court Architect. Why then dost think thou’dst be exempt?’

‘But, Your Highness, we are both reasonable men. Er, people. There is heaps of water. How can I be expected to draw with soiled hands? And wallowing in our own filth like sows? Why, that is but an invitation to disease. I implore Your Highness not to depart from basic principles of sanitation.’

‘Hold thy tongue, servant. I have reached the end of my patience with thee. Where is the temple that was promised me?’

‘I have not yet completed its plans, Your Highness.’

‘And when wilt thou complete these plans?’

‘Oh.’ The Architect would liked to have said three months. ‘Some days yet. You cannot rush perfection, Your Highness. Rome wasn’t built in a day.’

‘I shall see these patterns thou hast been drawing on thy vellum.’

‘And why shouldn’t Your Highness see them? I’ll just fetch them for you.’

When King Othon saw the drawings, he was thoroughly perplexed.

‘Naturally, Your Highness, for the layman, such drawings may be difficult to interpret, just as someone unschooled in the reading of music cannot possibly appreciate a Beethoven symphony by staring at the sheets. Let me do my best to explain it to you, if we start with the piano—’

‘Why presumest thou that I cannot understand these markings? Am I not the King? Or dost take me for a rustic dirt-scrabbler that cannot count his steps back to his filthy hovel, or remember a litany from one day to the next?’

‘Oh, Your Highness! How your words smart. Dear me, no. We are both men, people, of culture and education. I consider us equals. I shall therefore step back and allow you to examine the drawings with your expert eye.’

There was a long pause while the King stared down at the drawing under his nose, not looking at it, however. He felt his head swelling until it might burst. ‘Equals?’ he said quietly. ‘I heard thee say equals. Tongues are cut out for lesser blasphemy in Ratona, thou unruled and uncouth foreigner. No one but God, of whom Othon is the son, is Othon’s equal.’

Alfred A. Brussel cleared his throat. ‘Your—’

‘Prostrate thyself! Slug!’ The King had risen like a storm cloud. His eyes glinted menacingly under the heavy eaves of his brows as he aimed his forefinger at the floor. The Architect flung himself down. ‘If it pleased Othon, he would trod on thee, as he would stamp on a beetle, and trample thee.’ The King had indeed planted a foot on the head of the prostrate and trembling Architect. He pressed it down mercilessly. ‘Thou’rt worth less than a rub with a bow-legged market whore. I would use thee as my footstool. I would use thee for a mat to clean the muck from my sole. I would trample thee like a weed, or squish thee like a cockroach. No one in Ratona has his life, except by leave of Othon. Now, rise on to thy knees, bug, and harken well. Thou shalt put away these idle scribbles and abstain from thy carnal pleasures and thou shalt build my temple. When the Moon is eared again as it shall be eared this present evening thou shalt have built my temple.’

For once Alfred A. Brussel had no ready answer. Still lying on the floor, he gasped like a fish drowning in the air, while the King lumbered wearily to his seat. His wrath had flashed, then quickly subsided. Now he looked weak and elderly. The Architect attempted a conciliatory chuckle. ‘Your Highness jests. Ha-ha. Are we two Turks in a bazaar bartering over a carpet? You offer fifty lira, I say a hundred. We settle in the middle, and each believes he got the better of the other. Yes, you understand as well as I how the game is played, Your Highness. I cannot pull the wool over your eyes!’

King Othon’s eyes glinted fleetingly as he glanced up, a signal Brussel failed to notice. When, immediately following, Aldao was escorted into the room, the Architect was no more than slightly puzzled. Charming young Aldao, ever cheerful and full of play, now looked nervous, if not downright frightened. He sent an imploring look to the Architect. Alfred A. Brussel’s face blanched under his rosacea on seeing the flashing sword blade. He backed away, screaming. Aldao had not had time to scream, but only to gasp, before his lean torso was sliced diagonally. His entrails were yanked out and his corse flung down before the King. Brussel continued to scream until one of the rats delivered a sharp blow to his chest, winding him.

‘When th’eared Moon returneth,’ said King Othon, and clapped.

The Architect was barely aware of his feet being lifted and his body dragged from the privy chamber like a slaughtered bull from the ring.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.