Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

Alfred A. Brussel, heaped with wealth,

bids adieu to another grateful nation.

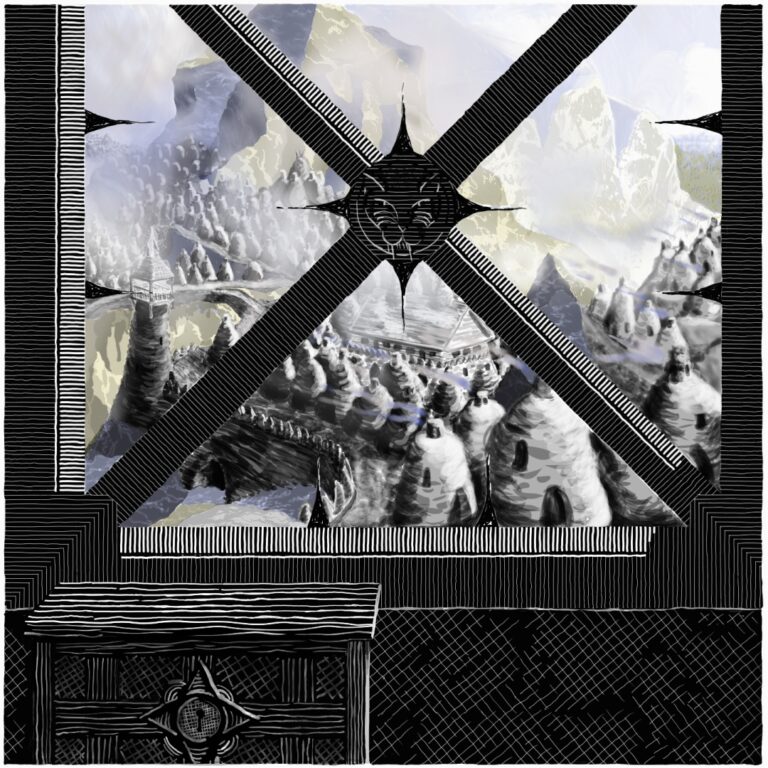

Alfred A. Brussel passed a snug and agreeable winter in the city of the cats. Indeed, there was no possibility of leaving. The snow lay thick all around. There were frightful blizzards. His house was cozy, however, and the fires were banked high. He had Nayel for company and amusement. They were invited to many soirées, for it was with parties, games and dances, and hearty eating and much guzzling of hot cider, that the nobility of Kitania passed the season. On fine winter afternoons there was sledding and skating. The short days closed with bumpers of spiced wine and singing round bonfires. Brussel was welcomed everywhere. As for Nayel, it was almost overlooked that he was a rat. Brussel himself hosted many fêtes, hiring musicians, jugglers, dancers and clowns for these gay revels lasting all night and into morning. In March, however, Old Man Winter was losing his vigour, the thaw was on its way, and the mountain passes soon would re-open. It was time to think of leaving.

The Architect had not, however, seen the Queen in a while. Indeed, he felt that she had been neglecting him of late and he was a little miffed. With the social season drawing to a close, he was growing bored and restless, but he expected a send-off as spectacular as he had enjoyed from Orthon. Then, too, he still hadn’t received the treasure she had promised.

Taking the bull by the horns, the Architect penned a short, rather brusque letter, stating his intended departure. He handed it to Nayel. ‘See that gets delivered to her nibs. Also, be sure we’re ready to leave next Tuesday morning.’

Promptly he received answer from the Queen, summoning him to her Bed-room of State. She apologized for neglecting him and explained, ‘We and our generals have been much preoccupied planning our campaign ‘gainst the rats. We wish to strike come Autumn. Indeed, I had expected thou wouldst be here to celebrate with us our victory and to slurp with us the fat of the Rat King’s thighs in our grand temple. ‘Tis an occasion I wait on eagerly and did hope it a triumph in which thou too wouldst wish to delight.’

‘Truly, Your Grace, I cannot imagine anything gayer. Pressing business affairs call, however. The Holy Roman Pontiff needs an extension to Saint Peter’s and the Emperor of Saturn desires me to lay out a zoological garden.’

‘Oh, that is a pity. Thou must stay, natheless, long enough to meet the Duke of Castor. He cometh early in April, and I have told him much of thee in letters already. He hath expressed the greatest eagerness to meet thee.’

‘And who is the Duke of Castor, Your Grace?’

‘Oh, a great personage among the beavers.’

‘Beavers?’

‘They are an aquatic folk,’ explained the Queen, ‘rather like big rats, I regret to say. Natheless, we are in want of their services.’

‘Yes, I know what beavers are, Ma’am. And you are right, they are rodents, just like rats. For reason that their teeth do not stop growing and must continually be filed down.’

‘Yes, well, rodents or no, they are fanatic builders. Indeed, the Earl of Castor is avid to see thy temple with his own eyes. Thou must be on hand to show it to him. He and his engineers will have many questions concerning its structure only thou canst answer.’

As an American, accustomed to his liberty, Brussel did not particularly like the Queen’s rather imperious tone. He thought it showed a want of gratitude for all that he had done for her. He gave a curt bow. ‘I shall consider Your Majesty’s proposal and see whether I may be able to postpone my departure.’

‘Prithee do so.’

He thought of making a rejoinder to this, but could not think what, so he turned abruptly and strode out.

Thus, Alfred A. Brussel was present when the whole city, with much to-do that somehow grated on him, greeted the Earl of Castor upon his coming. The Architect, indeed, was party to the Queen’s reception. The Earl’s eyes, normally beady and small, enlarged noticeably on seeing Brussel, but he recovered his decorum rapidly and extended a courteous paw. After that, the Architect was required to shake paws with all the Earl’s civil engineers. As soon as he could politely do so, Brussel stepped aside, drew out his handkerchief and put it to his nose. To Nayel that evening he confided, ‘Nothing more odoriferous outside of a Persian bazaar could be conceived. The Earl must bathe in perfume.’

Next afternoon, Brussel was to give the Earl a tour of the temple. At the appointed hour, however, only the engineers were on hand. One of them in an apologetic tone explained that, much too the Earl’s disappointment, he had been forced to pass on the tour, owing to pressing business with Her Majesty. This Brussel distinctly felt as a slight, that he had been ranked with these civil engineers who were no more than journeymen, not much better than domestic servants, really. He may as well have been appointed tour guide to a gaggle of charwomen and scullery maids! Fortunately, he had thought to bring along Nayel as a kind of lictor, to add lustre to his office. Nayel had the ceremonial job of following three steps behind the Architect, punctuating an appropriate gap between Brussel and the engineers, whilst carrying a symbolic measuring rod, a roll of drawings and a satchel with the Architect’s reading glasses and a few other unneedful implements.

The beavers did not disappoint Brussel’s expectations. They asked uninspired questions and made banal observations that revealed they missed the point, like a branch manager from Cleveland visiting Rome and, walking away from the Pieta, muttering that Michael Angelo had made the Virgin too big. Also, they all had small, rheumy eyes that they blinked frequently, which made Brussel think they suffered from short-sightedness.

When the tour was finished, the chief among them said, ‘I think we mutht be but unlearned and undetherving thpectatorth of thy art, thir, being thimple builderth of thivil thructurth, damth, earthworkth, tunnelth and mineth.’

Brussel nodded in agreement and, feeling friendlier now that they were parting company, said with his customary largesse of spirit, ‘Sir, never slight your honest profession. The yeomen are as needful to the commonweal as the knight. The town must have its stables as well as its churches. Moreover, the plainly utilitarian structure can add picturesque charm to wood and dale, or an appearance of happy completion to a riverine scene, so long as it is executed honestly, handsomely and with sensitivity.’

‘We beaverth like to think tho. Indeed, ith it not tho that the meek and mild milkmaid can have ditharming charmth that eludeth the fuththily coifed and rougthed thatelaine?’

This made Brussel’s brow frown a little. ‘Indeed, indeed. Nayel, are we ready?’

‘Perhapth, thir,’ ventured the engineer, ‘One day we may have the privilegth and great pleathure of thowing you thome of our damwork.’

‘Sir, I can imagine nothing more educational,’ replied Brussel, amused by the idea.

The Chief Engineer’s sentiment proved more prescient than Alfred A. Brussel could have dreamed, for next day he was summoned by the Queen. She was standing at a table examining plans, along with the Earl of Castor.

‘Ah, here be our Court Architect now,’ she said. ‘Would you cast your eye over these plans, sir, and offer some practical advizement on their improvement?’

‘What is this?’ asked Brussel, stepping up to the table and peering at the plans.

‘Thir, they are damth,’ said the Earl. ‘To be built in the river valleyth of her Majethty’s realm.’

‘A small surprise we are preparing for the rats,’ said Queen Katrina with a wicked smile.

‘Dams?’ Brussel stood frozen in place, wondering if it really was true that he had magnanimously agreed to postpone his leaving just so he could look at some drawings of dams.

‘We have summoned the Chief Engineer also,’ said the Queen. ‘He caneth perhaps answer what questions you might have.’

The next hour was one of the more unpleasant of Alfred A. Brussel’s professional career. From being closeted up with the Queen, the Earl and the Chief Engineer, whilst lectured to on statics and fluid mechanics, he went direct to his hypodermic needles.

After a week, the beavers departed. With them went the excitement in the city of hosting foreign visitors. It was time now for attention to re-focus on its rightful object, so, with much pomp Alfred A. Brussel took leave of another grateful city. He and the Queen chatted familiarly from their palanquins as they travelled through enrapturingly scented pine forests. The Queen’s retinue marched in front, Brussel’s slaves, carrying his treasure chests, followed in the rear.

‘What wilt thou do with all thy wealth when home?’ inquired the Queen pleasantly.

‘I must use some of it, unfortunately, to rid myself of vile creditors. But I will have lots left. I believe there is a great future in shipping. The modern reciprocating engine has burst open the transatlantic trade, Ma’am.’

The Queen shook her head ruefully. ‘Thy country is so much different from our own, Green Eyes, I cannot pretend to understand much of what thou sayest of it.’

‘Perhaps one day you can visit it, Ma’am.’

’Perhaps I shall. I suppose thou hankerest for it greatly, having been absent so long?’

‘Oh, indeed Madam. There is no place like home!’

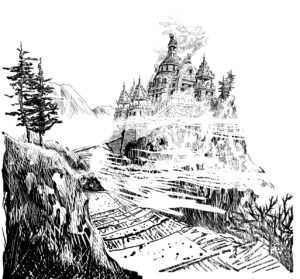

They stopped for the night at High House, the Queen’s residence where she often retreated in the height of summer, standing not only at the highest elevation of her realm, but also on its frontier. It was built like a castle, for it guarded the pass that led into Kitania. It was this remote stronghold that the Queen said must regrettably be the setting of their leave-taking. As they entered through the gate, the Architect admired the lofty massy outer walls of the fastness and in the court-yard he praised the excellent stonework of the keep. The Queen smiled demurely and said all was prepared for their coming. They took rest for a few hours to refresh themselves. In the night, a great banquet awaited. Music and entertainments lasted well into the next morning.

Brussel was awakened in the morning by the sun sliding clear of a peak and stabbing his face. He opened his eyes, annoyed. He found himself in a comfortable bed he did not remember having climbed into. Nayel still slept profoundly in his cot at the foot of the grand bed. Rising, Brussel slipped on his kimono and stepped out on to a long terrace populated with potted yews clipped into basilisks and other fantastical beasts. Hydrangea in full bloom climbed the walls of the house. Hearing the plash of a cascade, he went to the balustrade and leaned over. There was a dizzying drop. A stream of white water erupted from the basement of the house and arced gracefully before diving into the infinite depths of a chasm. Euphorically Brussel inhaled the freshness of the spray, the ambient perfume of flowers and coniferous needles. He ran his fingers along the smooth stone of the balustrade as he strolled to one end of the terrace, then turned and walked to the other end. Both ends were closed off by wings of the house, so he returned to his bed-chamber and rang the bell. A rat slave appeared on the instant and bowed low.

‘I hope it’s not too late for breakfast?’

‘Nay, Sire, the whole of the house is at your disposal, and the hours of the day servant to your wishes. With what would please His Worship to break his fast?’

Alfred A. Brussel rubbed his ample belly and thought on this important question.

Two poached eggs, four rashers of bacon and a hot gooseberry pasty later, Brussel leant back in his chair, sipped from his mug of beer and contently regarded the view. The salon of his apartment, high up in the keep, had a pair of French windows, opened this bright, crisp alpine day, on to a balcony overlooking the court-yard. This, howbeit, was not precisely the view the Architect admired. His treasure chests stacked to one side of the room were what pleased him. A slave entered to clear the table. Nayel rose to assist.

‘Is her nibs up and about yet?’ asked Brussel.

‘That I know not. Her Majesty is not here, Sire,’ answered the slave.

‘Oh. Has she gone out?’

‘I know only that she did not pass the night here.’

‘That’s odd. We were to take the air this afternoon. She was going to show me a very pretty lake nearby.’

‘No doubt she shall return shortly,’ said the slave.

‘Perhaps the explanation is in her letter, Your Worship,’ remarked Nayel.

‘Which letter?’

Nayel indicated an envelope on the mantle-piece. ‘I noticed it lying there earlier. It has Her Majesty’s seal on it. Shall I bring it to Your Worship?’

‘I wish you would!’

Alfred A. Brussel broke the seal and unfolded the letter. To his surprise, it was rather lengthy. He smiled, nodding approvingly, as Her Majesty opened with effusive praised of his genius. She had no doubt that there would never be a temple to rival the one he had created for Kitania. The only exception, of course, would be another springing from the same font of genius. This was what troubled her. Brussel frowned as the letter’s tone turned apologetic. It was not that she did not trust Brussel. She knew, nevertheless, how hot the Rat would be to out-do her. When he reached the bottom of the sheet, Brussel felt muddled and had to start at the top again more slowly. After reaching the close again, he looked up at Nayel with a dumbfounded expression.

‘Is it bad news, Your Worship?’

Brussel sat back heavily in his chair, his mouth hanging open. Despite the French windows’ being open, there did not seem to be enough air in the room. Nayel watched in bafflement as the Architect rose and walked to the balcony. He looked down at the enclosed court. He looked up. Directly across from his apartment, two guards on the outer wall seemed to be staring directly at him. Beyond them were the endless stone ramparts of the austere peaks.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.