Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

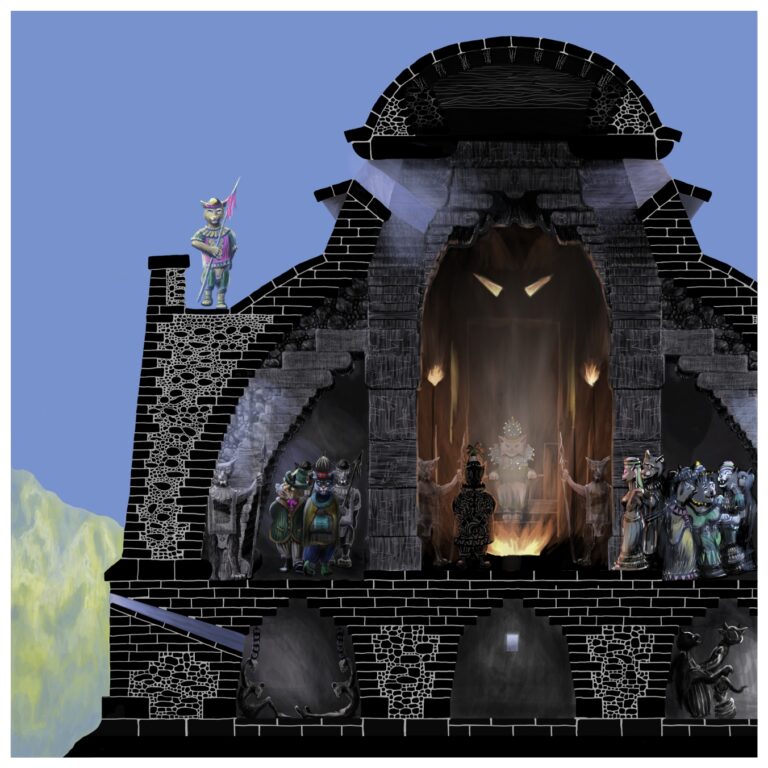

After a grateful rat nation giveth a rousing

farewell to the Architect, he calleth on the Cat Queene.

King Othon presented Alfred A. Brussel with a gold medallion on a chain in recognition of his service to Ratona. He gave him also a chest of treasure, four strong slaves and three rat wives who were attested virgins.

‘Your Highness’s magnanimity renders me speechless. I am moved to tears,’ said Alfred A. Brussel, glancing affectionately at the heaped gems. ‘However, I cannot dream of taking three chaste maidens of such peerless beauty, thereby robbing deserving rats the delight of their affectionate embraces. Nor, indeed, is it the practice of my country for men to have three wives, for the cost of so much lace lingerie and French perfume would be crippling. I will take one wife only. In place of the other two, perhaps you could add another two slaves. And if I might take Nayel from you as well, and maybe just one more tiny chest of treasure.’

His Highness was pleased to grant the Architect his requests. ‘I only regret,’ quoth he, ‘that I cannot persuade thee to abide here as our Court Architect. I would ecompensed thee munificently for thy services. Thou wouldst be a lord with much land and many slaves.’

Alfred A. Brussel bowed. ‘Your Highness, I will ever be at your service, whenever you have need. However, public life does not suit me. I plan to retire to a quiet life by the sea. There I will build a small house, simple and modest, albeit critically-acclaimed in architectural circles. I will grow my own garden and paint seascapes, have my glass of Madeira by the hearth in the evening, retire early, and hope to live to a ripe old age.’

‘And much tranquility and contentedness I wish thee, my friend,’ said the King, ‘in this new life.’ He then handed Brussel a rolled parchment. ‘This writing signed by mine own hand nameth thee a friend of all rats and giveth thee leave to go whither thou willest in all my realm, and furthermore commandeth whomever thou may encounter to aid thee on thy way by all measures in their power. Now kneel, Court Architect, and I will bestow on thee my royal blessing.’ When he had done so, Alfred A. Brussel rose, and he and King Othon embraced each other affectionately as brothers. Every eye in the place was damp, Brussel weeping the most copiously.

Early the next morning, which is to say at half-past ten, after Brussel had broken his fast, he and his accompaniment rowed in two canoes with high gilded prows down the Great Canal to the cheers of all Ratona and passed under the city gate. He had his little rat wife, six slaves, Nayel, his treasure, all his personal belongings, provisions for the journey, the loan of a palanquin with six bearers, and a scout. The mood was festive as hundreds of canoes and barges accompanied them across the risen lake with much chatter and laughter, music and song, and hails of farewell. Brussel wiped a tear, and affectionately caressing the top of Nayel’s head, fetched a deep sigh and said, ‘I almost misgive my decision.’

The final leave-taking took place at the lake’s edge. The shouts of farewell faded until only the gurgle of water parted by the prows of the two lone canoes was heard as they skimmed the narrow channels of the fens. Then they entered a broad river that seemed asleep under the hot sun, but it flowed with surprising swiftness, gorged by the recent rains. Rustling boughs overhung it, wherein avian folk warbled lays of love to one another across the water-way. Fresh verdure lined the banks, whilst here and there in splashes of light gorgeous flowers had opened to feast upon the sun. The travellers landed their craft to take repast upon a grassy field beneath the shade of some trees. When they had eaten, Brussel brought forth the King’s letter and waving it before the company, declared, ‘I have been charged by His Highness with a secret mission to deliver this letter to the Cat Queen. It demands her immediate surrender and obeisance, else he will make war on her realm and annihilate the puny remainder of her army.’

This declaration was met by long and appalled silence. The Architect invited the rodents to examine the letter for themselves, knowing none could read. While the other rats wore faces of the doomed, Nayel said, ‘Master, if we take such a message to the Queen, we will never get away alive, except, possibly, yourself. She will bite off all our heads.’

Brussel rolled up the parchment. ‘She will not dare to touch a whisker of any of you. You are my property! Now, you must do the King’s bidding, or the lives you love so much will not be worth a cow’s pie.’

Here indeed was an awful dilemma for the distressed rats, and they assuredly wished they had never been born. Half of them had a mind to run away at once and live as renegades, but they knew Othon would not fail to hunt them down, where-so-ever they hid, and string their heads over the doorway of his new temple.

‘You have all seen something of my power,’ pursued Alfred A. Brussel. ‘You must know that the Cat Queen cannot harm me or mine. Why do you think it was me that His Highness appointed as his envoie?’

He had not won them over. They looked at each other with wide eyes, but saw in each other’s glances no signal of what to do. ‘Master,’ said Nayel,‘ might we discuss the issue among ourselves?’

‘What? No! You have nothing to discuss. You are subjects of the King! Why, I might as well ask my luggage whether it wants to come with me!’ He wiped his greasy fingers on a cloth, sat on his rock and tapped his fingers on his thigh, impatient for an answer, but the rats, hanging their heads, found the situation too tragic for words. ‘Very well,’ said Brussel decisively, rising to his feet. ‘You’ve had your chance. I at least shall not break my fealty to His Highness. So saying, he retrieved his portmanteau from the canoe, and giving a curt nod to the rodents, tramped off. He fought his way through some underbrush. By the time he had pulled his portmanteau free on the other side, he was hot and frustrated and felt that he had already had enough. Before him ascended a steep bank. Tightening his grip on the handle of his portmanteau, he resolutely started to climb, swaying wildly to keep his balance. He made it half-way up when he lost his footing on the damp herbage and slid back down on his belly, his portmanteau still half-way up the slope. With his hands freed, however, he found it easier to climb back up to his portmanteau. He decided it was more efficient, and safer, to fling his portmanteau up the hill an arm’s length at a time, then pressing down on it both as support and to prevent its sliding back down, to follow with his legs, then repeat the manoeuvre. At this speed, it would probably take a year to reach Kitania, he thought crossly. Then to his eternal relief he felt a helping hand under one of his arms, and there was Nayel beside him. The Architect was struggling far too much and was far too winded to say anything until they had reached the top of the embankment. Then, when he had caught his breath, he hugged the boy as he had never hugged him before, for though this was exactly the result he had calculated, he was overcome nonetheless with gratitude. ‘Bless you, my lad, bless you.’ Then they were met at the top of the hill by all the other rats, who had chosen an easier and faster route of ascent, looking shy and repentant, for once Nayel made his choice, weak in their own resolve, they had submitted to his lead. Brussel heartfeltly grasped the arm of each rodent and beamed at him. So reconciled did he feel, so much comradeship did he sense he had with them, that when they set out, he went on his own two legs, as one of the lads. They had journeyed an entire mile and a quarter before he decided to get back inside the palanquin for a breather.

In such wise they turned aside from their seaward path and travelled high into the mountains, coming to the fastness of the Cat Queen.

The bizarre creature bowed low, flourishing the emerald hat she recalled seeing. ‘Your Majesty, I was the chap who flew over your capital in a hot-air balloon.’

‘Indeed? Whence came you, sir?’ asked Queen Katerina.

‘Majesty, if I may implore the indulgence of a few moments of your time, I will tell my story briefly. My name is Alfred A. Brussel. I make my home, Your Majesty, on the planet Mercury. There I have devoted my time to mastering the art of architecture, and that so successfully that the capital city of my home planet is embellished with many of my works: libraries, hospitals, planetariums, halls of justice: all temples, Your Majesty, to our Goddess of Reason. I was on my way to visit the Archduke of Tennessee, for, knowing of my renown, he had retained my services to create an academy of oceanic science on the shores of his country. Unfortunately, I was blown off course by an evil wind. My vessel crashed, as undoubtedly Your Majesty witnessed from your city. I was captured by the rats and was in imminent danger of being disembowelled when their barbarous Rat Chief, learning my name and knowing of my repute, instantaneously commanded me to design for him a temple that would trumpet the power and glory of the Rat God. As his prisoner, my continued existence mercy to his heathen caprice, I had no choice but to submit to his behest. That I superseded his expectations is attested by his gifts to me of treasure, a rodent princess and slaves that you know to be in my possession. Indeed, I take no little gratification in being able to inform Your Majesty that the lavish setting wherein your royal consort and all his captains were sacrificed was entirely compatible with its illustriousness victims. That temple, Your Majesty, eclipses the holy dwelling place of your Goddess as the Sun stuns the remainder of the firmament, which he simply annihilates with his piercing rays. I do not pretend to be a modest man, but I am no braggart either. I state to you the square facts.’

‘Why, then, sir, thou art the detestable foe of all cats,’ quoth the Queen. ‘And I am in perplexity that of thy own election thou knockest at my door and so frankly offerest me thy meats. Seldom hath my game so obliged me as to do the pursuing. Dost intend to skip into my oven withal and baste thyself with thine own juices?’

‘Nay, ‘tis friend that standeth before you, not foe, offering himself to Your Majesty’s service,’ said Brussel, bowing devoutly, then, recalling to mind that he was a modern and free American, straightened himself and, recovering his accustomed mode of speech, proceeded thus: ‘My people despise rats just as much as do cats. We are natural allies against the vile vermin. If I had not obeyed the commands of the Rat King I would have lost my life, as I just explained, and had I lost my life, Your Majesty, Your Majesty would not have the benefit of my services. I offer you my head, so long as Your Majesty agrees to its remaining attached to my neck. I put at your service my eyes in their sockets, my nimble fingers, and all the science and art treasured up in my brain. My Queen, listen to me. You know you were robbed of your prize by a perverse turn in fortune. But the current circumstances are unnatural and cannot long endure. A poor card player can win a hand through luck, but he cannot win the pot. Cats are the natural superiors of rats. Kitania’s wounds will heal. Kitania will rise again, she will redress her wrongs, revenge cruel fortune, and conquer. I hazard to say, Your Majesty, I only speak your own mind.’

‘My thoughts be easily guessed, sir, and need no clairvoyance to divine. This defeat was an affront that cats cannot endure to go unpunished. I will be so frank with thee as to acknowledge ‘twas in great part owing to the recklessness of my consort. He thought he could bully fate into winning him the prize in one grasp. An humbler captain would have adjusted his play on seeing how the hand went, wagering to lay siege to the city when outright sacking of it seemed foredoomed. He would not have lost me mine army nor mine helpmeet. But I need not a foreigner to teach to me mine own thoughts. Now come, short delay doth whet the appetite, but long doth dull it, so serve the meat of thy matter, I do implore thee.’

‘What real satisfaction will Kitania enjoy, knowing, Your Majesty, that, when the lords of Ratona are sacrificed, and indeed the obese Rat King himself is served on a salver, the dining room in which their flesh is consumed is a chicken coop compared to the grand saloon where your own kin and kind were salted and peppered?’

This made the Cat Queen cross. ‘Sir, thou hast not seen our temple, methinks.’

‘Methinks I have, Your Majesty. I saw it from the air, remember? I cannot help but think your Goddess must be ashamed of it. Would you, a great Queen, consent to receiving foreign heads-of-state in a barn?’

This made the Cat Queen furious. She knew not how to answer an insult that might well be true. Rumour had indeed reached her ear that some heavenly mansion fallen into their stinking city had won the rodents the favour in the late contest. Furthermore, she had seen this grotesque creature fly over her very head suspended from a floating ball, so it was scarcely credible that it lacked any magic power whatsoever, a consideration which made it imprudent to completely discount its vaunts. The Queen, albeit, not wishing to reveal her bruise, chose not to exercise her temper, but said mildly, ‘Sir, thou dost drive thy points with little subtlety and not without sting.’

‘Sycophants and the mendacious are skilled at subtlety, Your Majesty,’ returned Alfred A. Brussel, with a polite bow. ‘I am an American. A Mercurian, I mean. We are an honest and direct people.’

‘Let us desist from batting the shuttlecock at each other,’ quod she. ‘I pray take thee to thy rest, sir. To-night let us dine together, that we may discourse at greater leisure on this matter.’

‘You do me a great privilege, Madam. Before I beg my leave of you, may I inquire as to the well-being of my train?’

‘The rodents?’

‘Yes.’

‘They are in prison, I speculate.’

Of course. But may I entreat Your Majesty to see that they are not ill-treated? And that they are fed? They are my chattel.’

‘The Queen of Kitania, sir, does not trouble herself with the well-being of a few scurvy rodents,’ said she indignantly. ‘Howbeit,’ she relented a little, ‘I will have a word relayed to the jailer that they should not be unduly flogged, nor that they be breaded and fried, deprived of their vital parts, nor starved.’

Alfred A. Brussel bowed. ‘Most kind of you, Madam. And at the risk of trying your patience, there is one of them, of special interest to me. May I have him back?’

‘Impossible. Rats do not go free in this city. They are kept in a jail or in the larder.’

‘He is a harmless youth and would be under my watch, Your Majesty. He has particular knowledge of my wants.’

The Queen was indecisive. It was true that, despite what she had said, there were rats in the city employed as slaves, beasts of burden, or target practice. She was not, however, yet sure how far she should trust this unexpected and not entirely welcomed visitor. ‘I will hold thy request in consideration,’ she said after a pause, in a tone that made clear the matter was for the moment closed. She rose, and so ended the audience.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.