Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

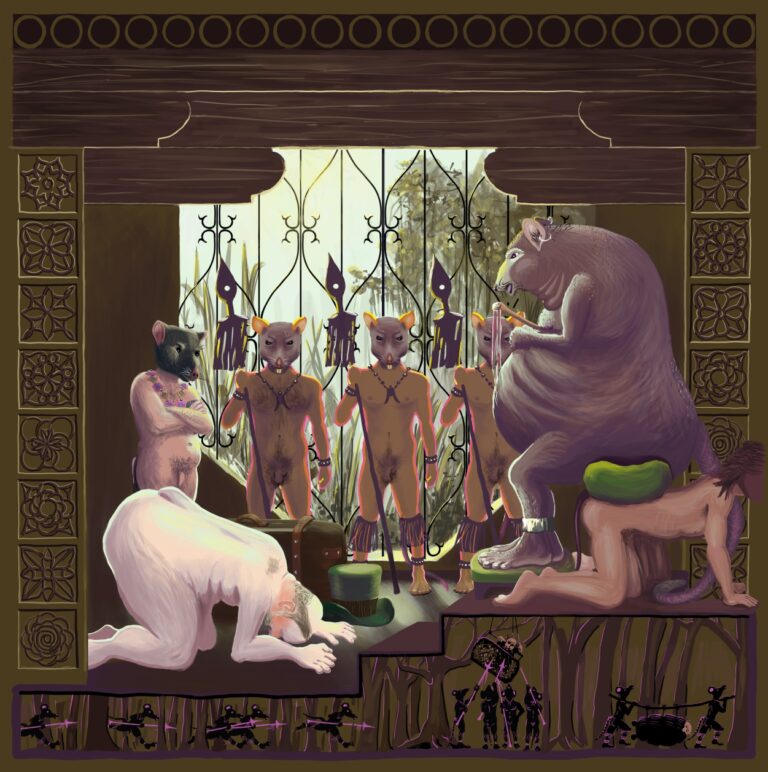

The pilot of the strange craft is carried to the

Grand Rat, to Whom he tendereth his services

in exchange for his life.

The plummet of the celestial object had caused a stir also in the city of the rats, where it was thought that this was some new instrument of war of the cats. No instructions came from the palace, however, forbidden as it was to disturb the King for any reason. The Lord Etiam therefore went forth with a party of his rats to steal up on to the place where the thing had fallen. Upon his return, three days later, he insisted, ‘I must see the King.’

But His Highness’s Groom of the Stool said, ‘The King hath lost his nephew and his son. He speaketh not even to me, who am his most loved servant.’

So the Lord Etiam said, ‘The kingdom’s business taketh no account of its King’s sorrow, but driveth on relentless.’

‘Tell me this business,’ quod the Groom, ‘and I will speak it to the King’s ear when the moment is opportune.’

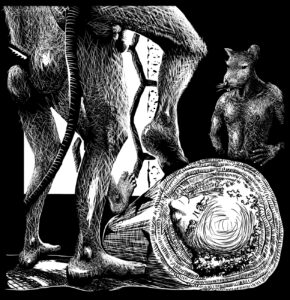

Whereat the Lord Etiam made a sign to have carried into the chamber on the shoulders of four of his rats what appeared a roll of carpet, but of finer stuff and more brilliant hue than any in that chamber knew, that it seemed weaved in an heavenly loom. When the bearers relieved themselves of their burden, allowing it to thud to the floor, it emitted a muffled groan.

‘What be this, my Lord Etiam?’ said the Groom of the Stool, much surprised.

Lord Etiam bade his rats unroll the bundle, which they did roughly by kicking with their feet. He said, ‘Show the Groom of the Stool what creature’s be this cocoon, that erstwhile did charm the air with its flight, but now hath reversed itself from butterfly to most repulsive worm.’

They set the creature, helpless, for they had bound it with cords, upon its feet. Then the Lord Etiam set upon its head its emerald cylindrical hat. ‘This be its outlandish headpiece that it wore when we did come upon it.’

The Groom of the Royal Stool stared fearfully at the alien creature. ‘Why hast thou gagged it? Can it speak?’

‘Most volubly it canet,’ Lord Etiam answered. ‘Ten words in the space between two of thine. What it cannot do, damnably, is hold its tongue.’

‘And what doth it say?’

‘The rarest things conceivable. My rats pled leave to stop its mouth, for fear of its casting some spell.’

‘What is it?’

‘A kind of cat, Your Worship.’

‘A cat?’ said the Groom of the Stool dubiously. He was no expert on cats, for having not left the palace in thirty-seven years he had never seen one live in the flesh. He had seen carcases, and he had seen, of course, those costumed dramas where the cat, played by one rat seated on the shoulders of another, was so easily dispatched once the rat hero had paid the proper devotions to the Rat God. ‘It doth have the whiskers of a cat and the great bright eyes of a cat,’ he allowed, ‘yet . . .’

‘Not like any cat from these parts, in sooth,’ admitted Etiam, ‘but a cat natheless, from over the mountains, where many more fabulous beasts than this monster do abide.’

‘It hath no pelt,’ observed the Groom.

‘Oh, but it had, Your Worship. It was quite loosely attached and peeled clean off in the tussle.’ Then Lord Etiam signalled for the coat to be shown the Groom. ‘We had a lusty fight of it before my lads subdued the divil, bless all their hairy balls.’

The Groom of the Stool raised his brow, for the coat was bright emerald like the hat. ‘And you have its tail?’

‘That was torn to pieces in the fight, my Lord. The brute fought like one of hell’s own goblins. I couldn’t be prouder of my boys, every last one of ‘em braver and brawnier than a goddam bear.’

Now, the Groom of the Stool, sheltered life though he led, was not the King’s most trusted advisor without reason. He could see very well that the beast’s claws were blunt, that the thing was pudgy and that it bore no visible injuries from the reported battle. Only its eyes, that were indeed feline, and bright as live coals howbeit emerald, like its coat, seemed possessed of power. The Groom of the Stool concluded that the Lord Etiam was a little too lavish in praising his lads’ testicles. He wanted to see the thing’s fangs. ‘Ungag it,’ he bade, ‘and let us hear it speak.’

When they untied the string and pulled the wad from the creature’s mouth it blurted, ‘Oh, Mercy sakes, what a relief! My mouth feels like my poor mother’s twat after delivering me to this Darkening Plain and Vale of Tears. I have the honour of standing before His Highness’s Groom of the Royal Stool, I gather? Alfred A. Brussel. Architect. A pleasure to make your acquaintance.’ Then it held out its doughy and hairless pink paw. However harmless it looked, the Groom of the Stool shrank back from it. Moreover, he was utterly overcome with surprise to hear the miscreant speak, just as if your grilled perch had decided to salute you from your plate.

‘Ah, not the custom, I see, in these parts?’ said the repellant being. ‘I understand completely. Don’t worry, you’ll find me a quick read. In Rome, etcetera. In Constantinople don’t mention the Pope. In Athens don’t bend over. When, if I may ask, shall I have the privilege of waiting on His Highness? I trust such a tremendous pleasure will not be long in coming. I have no doubt that the exchange of ideas will be an edifying experience for us both.’

The Groom of the Stool could not help speaking of the strange and garrulous thing to the King. The King wanted to see it.

Chimes sounded from behind an arras, alerting all in the presence hall of the King’s imminent apparition. A brace of stout rats entered first, then two more, one with a sheaf of straw, the other a cushion. The first two, grand-nephews of the King, had the privilege of dropping on all fours, posteriors to the court. The cushion was laid upon their buttocks. To the rattle of a rattle-stick King Othon lumbered in and two attendants taking each a sacred arm of the divine manifestation lowered him upon the cushion. The drudge with the straw, a bastard of Prince Driscoll, cousin to the King, had charge of shooing flies from off the Great Rat.

‘What is it?’ he demanded of the court, not looking at anyone in particular and particularly not ‘it’.

‘Your Highness, may I be so bold as to introduce myself? I am Alfred A. Brussel,’ it said.

The court was transfixed, both that the thing should speak before commanded and that it could speak at all.

The King stared, as one who thinks he glimpsed a cockroach. ‘What is a brussel?’

‘No, no, not a brussel, Your Highness. Ha-ha. I understand the confusion. No, I am neither vegetable nor mineral, but animal. Brussel is the surname. In point of fact, I am an architect. That is, an inamorato of Her Ladyship, the Queen of Arts, her pursuer, disciple and prisoner, an old and loyal retainer, a peacock in her garden, a carp in her fountain. A monkey in her boudoir. To delight her, to give her pleasure, is why I exist, like the dildo in her bottom drawer. I am owned by, bound to, entranced by no other mistress than she. Clear as shaving cream, I hope?’

The court had drawn back, giving a stage for the creature to strut and gesture, confident in having enraptured and bewitched its audience, albeit the rat folk were in horror and withdrew only to separate themselves from the anticipated doom.

Not becharmed one tittle, but disgusted, it was not any clearer to the King why he should not turn over the repulsive amphibian to his priests for immediate disembowellment. ‘After which, have the polluted carcase dragged to a remote place outside the city and burnt,’ he further directed, ‘till ashes only remain.’ Then, heaving a heavy sign, he waved a despondent dismissal, which served also to brush from his mind the disagreeable episode. He prepared to rise ponderously to his feet upon the arms of his attendants, intending to return to his darkened privy chamber, there to rejoin his mournful thoughts that he had briefly abandoned.

Brussel, appalled, dropped to his knees. ‘Oh, Your Highness, that would be a terrible pity. An architect is so much more valuable to you intact.’

‘I see no value in one at all,’ retorted the King.

‘Oh, but you will! You will! How Your Highness will rejoice at the things I can do!’

The King, still uncertain what an architect was, and mildly curious, remained seated. ‘What things be those?’

‘Let me explain. I did have opportunity to survey your city briefly as I flew over it, Your Highness. Granted, I have seen little of it at close hand, owing to the manner of my arrival. Moreover, the accommodations you have kindly provided for my stay in your friendly land do not have much in the way of view. Of course, that isn’t a complaint. Windows come with draughts and the likelihood of catching cold. I am sure your hospitable staff are thinking only of my health. There is much to recommend simple appointments and a frugal diet. What need has the body of red meat and wine? Buddhist monks live for a hundred years or more on a daily bowl of rice, while suffering none of the ailments that we do in North America owing to our rich diets. Of course, I am not saying I don’t enjoy a few luxuries as much as the next man, an indoor commode, running hot water. But the lusty farm lad, after an honest day’s labour in the fresh air, finds his mattress of straw as conducive to sleep as any feather bed with silk sheets, while the fussy debutante, who has performed no more exertion during the day than to lift her pinkie to drink her tea, tosses and turns all night. No! No!’ he cried, for he had seen King Othon make a nod to his guards. The guards drew up on either side of Brussel. ‘I promise to make my point briefly, Your Highness. I had opportunity to survey your city as I flew over it, as I mentioned, and I observed little evidence of your having the benefit of architects here.’

‘We have got on well without them, whatever they may be,’ answered Othon XVIII.

There was a sneeze from behind the King, and his cushion gave a violent shudder. Annoyed, the King gestured to be handed the sheaf of straw from the fly-swatter, with which he swatted the suspended balls of the offender.

‘Yes, yes, of course, Your Highness. That is what you think. And why shouldn’t you? I don’t suppose the Nebraskan misses the salt air of the sea. But, let me be so adventurous as to propose that Your Highness is mistaken and that you are in sore want of an architect. A royal architect in your service. I do truly and devoutly believe, Your Highness, that my unfortunate navigational mishap was, in fact, heaven-sent to help you. An architect, Your Highness, can elevate your nation to the highest rank of civilization. Noble works of architecture edify and delight.’

‘I have priests to edify me,’ said the King. ‘And when I want delight, I summon my dwarf, or lie with a wench.’

‘I realize, Your Highness how difficult it must be to imagine a cultivation completely absent from your land. I speak of a paradisiacal life derived from the contemplation of sublime and exquisite works of art, uniting the rarest spiritual pleasures with the sensual ones of the body. There is no other joy on earth quite like it, Your Highness, saving perhaps the orgasm, which however so rapidly evaporates. It is the one abiding consolation for all the tribulations we mortals must endure here in this wretched land of exile. In fact, it can only be compared to that bliss enjoyed by the Elect in Heaven.’

‘How camest thou to this knowledge? Thou hast visited this happy place, Heaven?’ asked the King.

‘These eyes of mine have seen it, Your Highness. They have seen mansions and temples and palaces undreamt of in your world of muck, brick and thatch. The eyes of the architect are the eyes of a visioneer.’

Othon regarded the eyes like emerald stones that stared back at him with feverish luminosity. They were eyes that might mesmerize one unwary of their trap. The King veered his glance. Then a thought occurred to him, at once exciting and unsettling, that in the lustrous green of those eyes was distilled all the vigour that had faded from his desiccated land after the rainless days that had cumulated till none but the priests might number them. He asked, ‘If this city be so wonderful, why didst thou leave it? Why chose thee hither to come, to this gross underworld of muck, brick and thatch?’

‘My dear Highness, the architect can make Heaven wherever he may find himself, with whatever stuff be at hand. Did not God make Adam from clay? But, to answer your question regarding my departure, it was forced on me. I was beset, you see, by creditors. They were harrowing me without let-up. I simply had to escape. A faithful friend of mind was so kind as to lend me use of his balloon. Unfortunately, he had no time to instruct me in any but the most basic points of its navigation before I had to make my get-away. Having no prior experience in aerostatics and limited knowledge of meteorology I found myself straying off course. My intended destination was Kansas City. Missouri, that is. I believe Denver was the last American city I saw before passing over the mountains.’

‘What are creditors?’ broke in Othon XVIII.

‘How disappointed my friend will be to learn of the destruction of his globe. Creditors? You are happy folk indeed if creditors must be explained to you. They are leeches, Your Highness, vampires that suck the blood. Always at large, hunting for their prey, widows and orphans mostly, and honest entrepreneurs.’

‘But if thou beest as wizardly as thou dost boast, why not destroy such plaguey vermin?’

‘Creditors cannot be destroyed, Your Highness. Cut off a head and two spring up in its place. They proliferate like bluebottles after a summer’s shower, like maggots on a hunk of rotten meat. One or two. Three or four of the pests, one can tolerate so many. But when a legion of them decide to harry you, and send their detestable bailiff, well, one must take to one’s heels.’

‘What is this thing called Bailiff? Much of thy speech is but riddle to me. Thou sayest to see, only to cast sand before mine eyes. Sayest thine Heaven be delightful, yet that it be full of leeches. We have leeches here, what want have we for thine? Makest offer of things I cannot desire, for how can I desire what I know not? I ask plain, and want plain answer: Canst thou give me back my dead son ? For that is a thing that I do desire. Vanquish me my foe? Canst break her altars? Bring back to us our absent God, and I will reckon thee a wizard of uncommon power.’

‘Yes!’ exclaimed Alfred A. Brussel. He had been looking increasingly despondent, but this last request brought back hope to his face. ‘That is the very think I have been trying to explain to you, but I suppose in my own funny, foreign way. Of course, it is the evocation of the divine that the architect undertakes.’

‘But I have priests to do that. Lousy priests who have been no use to me! They engage in abominable acts that disgust our God. They lie down with their sisters and break the dietary laws. Worse, the slinking felons spy on me and sell their information to the cats. How else came the feline brood to be privy to my son’s doings?’

‘Your Highness, I too am a priest. That indeed is what the architect is, a type of priest. But a higher priest serving at the twin altars of Science and Art, and whose results, therefore, are guaranteed, or else his fees are refunded. Now, your God, you say, has forsaken you. Hence, you have suffered these misfortunes you’ve mentioned. I am sure your deity is right now enjoying himself somewhere like Ungolia, where, as I understand, they have excellent architects. Now why, I ask Your Highness, when he is enjoying such good hospitality abroad, in a palatial setting far more befitting his divine rank in the pantheon of numinous beings, with excellent eating, and where, moreover, the climate is much more salubrious and less sticky than here, does it surprise you that he avoids the brick and thatched habitation you offer, with its dingy compartments and pestilent vapours? It’s a simple question of competition. Who is offering the better living arrangement?’

King Othon was silent and pensive. He could see that the architect had a point. Might he have been taking his God for granted? Hadn’t the Verger told him that the temple roof was beyond repair? And he had simply said, carelessly, that he supposed the roof could wait another season. He now saw that he had been treating his God in the same rather absent-minded, neglectful manner he did his wives whilst he wooed Mayte and sent her daily gifts. For this reason had his son died? His Highness was stabbed with sorrow and remorse, as keen and over-whelming as on the first day of the terrible news.

The Architect could not remain silent whilst his fate hung in the balance. ‘What is the cost of sparing me a little time? If I can restore some of the happiness you have lost with the help of the little arts I have mastered, will I not have recompensed Your Highness’s mercy?’

‘Enough,’ said the King, waving a hand as through shooing a mosquito. ‘My servants will want their midday meal, whilst I have other matters that need attending. I defer thy disembowellment until the morrow, whilst I take measure of thy proposal.’

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.