Thank you.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

HunGar Book Galley

By clicking HERE.

What ensued after the Prince & Lord Esan

Parted from their Brethren.

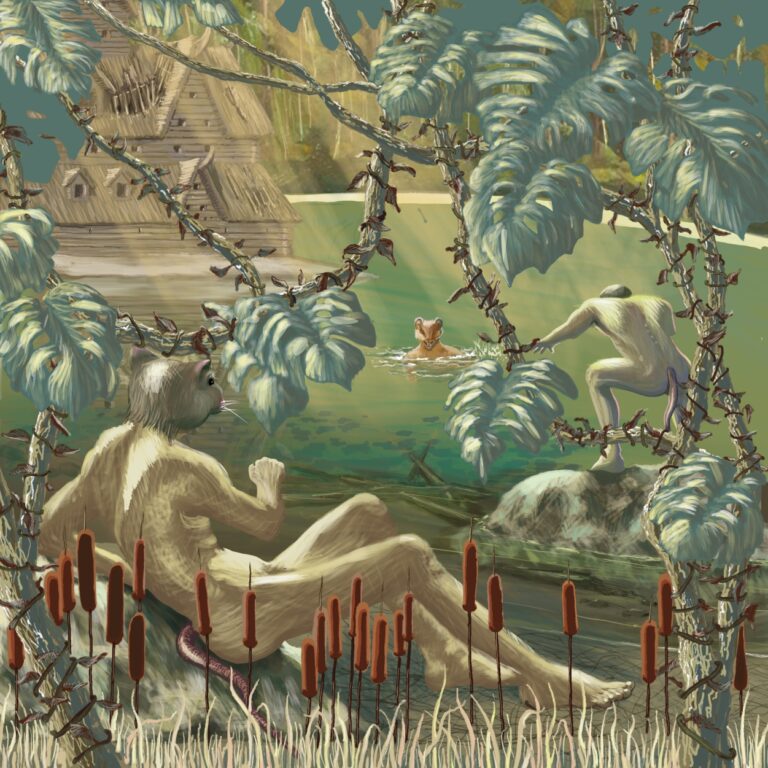

So they forked their three ways, Hranu and Esan and their rats going upstream. They spoke not, but only the water chattered as it skipped past. Either side all was watchful silence and no footed thing was at large as they filed past the gloomy shafts that were the deepest shades of burnt umber, porphyry, copper and iron, and blinding stabs of sun-light. Middle day they were come to a dam of logs and earth neglected and fallen into disrepair, and a pond glistering green as an emerald stone that was encircled by the brooding shadows of the forest, dark as the crow’s wing. At the pond’s centre was an island whereon a beaver house stood, abandoned withal. The sun’s rays’ being hot, and an inviting ripple on the pond as the breeze danced an antic on it, the rodents threw off their gear and plunged into the refreshing water, for rodents do ever love water and swim naturally as do the fish. They dove deeply, played rough house and leaped from the rocks, then drowsed on the warm bank to dry in the sun. But Hranu and Esan swam to the island to look over the grand old mansion, made of timber. They found naught in it to betray what came of its former tenants, but only scared up in an upper storey a tribe of flittermice that erupted into a storm of black wings.

Middle morning of the next day, farther upstream, they came upon a fishing net strung across the water. In the dried mud of the bank were impressed many paw prints. Caught in the net were a few fish that the rats eyed greedily, but the Prince Hranu commanded them to stillness and to keep their ears pricked. His body tensed as he stared at a place where a well-beaten path delved into the forest green. With hushed voice he said to Esan: ‘Cats,’ then remembered to look up into the branches, but among the web of limbs and intersecting stabs of sun-light he discerned no movement nor menacing shape. There was no birdsong, but that perhaps was for reason of their own coming, that the birds had fled.

‘What if it’s raccoon?’ asked Esan in voice a-tremble.

Hranu gave him a scornful glance. ‘Hast thou yet to learn cat’s paw from coon’s, nursling? And that reek of cat urine, canst thou not sniff it? And that worn path was made by a tribe of cats, not a solitary coon. It leads to their village or hamlet, not far off, I’d wager my prick and balls.’ The Prince in his excitation spoke with increasing rapidity, and his eyes shone with adventure. He ordered scouts to creep forward.

‘Dost thou intend to attack, Hranu?’ squeaked Esan.

‘And for what did we come this far, to play hopscotch with ‘em?’ Hranu answered.

‘I mean, were not we to make report of our findings to Etiam and Nahum, and return with our full force?’ sayeth Esan, and the young Prince, seeing doubt also in the eyes of the others that were giving ear to the exchange, waxed hot that he forgot his own commandment and burst out: ‘Fie! I should have left the babies back home with their nursies!’ Then, remembering to subdue his voice, in lower but no less vigorous tone said: ‘Whichever ye mice do wish may scamper to the paps of Etiam and Nahum, for ‘tis better for the bold few to have bigger helpings of the glory, but I know those twain will do liken if they scent game, and I’ll not be the milksop that meets up empty-handed! For shame! Are ye not champions of your nation? Or are ye paupered of birth that you tinkle yourselves in terror of a few inbred country cats that have wielded nothing but muck rakes nor shed any blood but that of the poultry in their chicken yard? They are napping in the sun right now, I wager you, gorged after their lunch and sleeping off their grog, and you want to turn arse. Scamper, I say, and let me not see your cowardly mugs again!’

But none did withdraw, but all stayed, looking ashamed and also frightened. Then quoth Esan, half-regretfully: ‘You are our liege, Prince Hranu, to whom we are bound in conscience. None have we but you to lead us.’

When the fair Lords Etiam and Nahum and the Lord Astre met again upon the streambank, discovered the Prince Hranu absent among them, they tarried one day in wait, then journeyed down current in hope of meeting him. They found no trace of the missing party till they were come upon the fishing spot. Following the path, they found dabbles of blood staining the leaves, the which did them greatly dismay. A little farther and they came on to a broad place where they saw the remains of a large feline camp. From the sturdiness of some of the structures that had been but half burnt and demolished they judged the camp to have been established for no little time, but also to have been quitted suddenly and in haste.

Spake Nahum: ‘Surely the Prince Hranu, discovering the foe so largely assembled, would have made himself scarce.’

‘So sense would have counselled,’ averred the Lord Etiam. ‘Yet my heart is heavy with the dread of the Prince’s acting athwart of sense and foolhardily attempting some daring feat of abduction.’

‘Mad, not rash, would have been,’ said the Lord Astre, ‘to commit a crime that must be discovered faster than a hare tops a doe and hot pursuit put on the tails of our fleeing friends. I’ll not believe it without further proof.’

Whilst Nahum continued down the creek, in hope of finding some sign that their brethren had escaped or evaded the cats, the Lords Etiam and Astre followed in wake of the army. Cats, howbeit, are swifter than rats, and this army was not tarrying, but was pressing with all speed into the foothills of the mountains, into the heart of the feline realm, where it was perilous for a small company of rats to venture, thick as it was with cats. So, with much reluctance, and hope dying in their hearts, they turned back to find their friends.

‘The enemy doth hurry to their capital,’ the Lord Nahum reported unto Etiam when they were met again, ‘to the seat of Katrina high in her mountain fastness, for which reason I do fear they have some special prize to bring their sovereign.’

‘These indeed be evil tidings,’ said Etiam. ‘Howbeit they confirm my own dread, for we happed upon no trace of our dear Prince’s retreating down-stream, but came across most dismaying signs of some three or four of the enemy’s scouts’ having followed him stealthily as he made up-stream towards their camp. He was spied upon by cats hidden in the trees the whole time, and the camp was on watch for his coming. Our Prince might have thought he had the advantage of surprise on his side, but ‘twas he that was taken unawares.’

Most sorrowful was the journey of the young lords back to Ratland and the watery city of their fathers. Piteous were the tears they shed for the lost brethren that they had loved. But the tears of Astre could not shed his grief, for that he had loved the sweet youth Esan with all his heart. Day-light, for Astre, food and drink and eke breath itself were now burdensome as prisoner’s chains he wearily dragged. The citizenry that followed them through the winding passages to the palace, there to deliver their heavy report to the Rat King, was a grim funeral march. King Othon exchanged with the returned lords but few words, then did graciously bestow upon them his blessing before shutting himself up in his privy chamber. Orders went from the palace forbidding all speech or noise in the public places of the city. The idle chatter and mirth that filled the frivolous hours of His Highness’s wives and concubines ceased, the youngest and gayest among them become as grave as elderly widows. Then, that night, whilst the city slept, the palace gates swingeth open and the King rideth out in his palanquin.

Silent as the fish that swimeth, swift as the skimming canoe, black as the crow that winget on the night, the shadow passeth through the slumbering streets, bearing for the loftiest of the five watch towers of the city walls.

Laborious was the King Othon’s climb to the top of that tower, lifted, pushed and pulled by his lackeys, all squeezed into the narrow stair that screwed up and up. On reaching the head, he staggered against a wall, wheezing, his pounding heart on point of bursting. Then, having somewhat recovered his breath, he dismissed his servants and behind them shut the door. He went out on to the balcony where the wind blustered. He stood there a long time, his chest occasionally heaving, though not now from fatigue. Beneath him the city stretched, so dark and silent, as if not rats slumbered in their houses, but the dead in numberless crypts in their dreamless oblivion. Not his own realm did the King fix his gaze upon, natheless, but on those primordial shapes frozen in the twisted torment of their fashioning, flattened by night and distance to a pasteboard cut-out fixed upon the starry sky. In morbid weeds of deepest purple they were draped, that the old, weak eyes of the King sought to penetrate. Then a sob clutched his breast, for with some sudden clearing of the air he discerned a dull reflection on one of the mountain flanks, like the stain blood might make upon dark lawn. He recalled seeing something similar once before, but then he had been no more than a ratling, scarce understanding the profound sorrowing it caused the city. He did now. The ruddy light faded and strengthened as vapours of air passed in the intervening space and as its source flared and diminished. The King murmured: ‘I will not leave thee. I will not leave thee.’

‘I will not leave thee,’ he repeateth after a space, as his eyes drop heavy. But instant as his lids drooped do fell sprites affright his ears with racket of hellish music, of drums beaten, cymbals clashed, trumpets screeching and the yowling of fiendish cats. Roaring as fell beasts, the red tongues burst leaping, scorching his lidded eyes. The demons, released from the pit on this night of witchery and butchery, beat the air with their fiery wings, riotting with their insatiable lust for live flesh and marrow. They wrastled over their spoils, tearing the victims asunder between them whilst howling with ravenous fury. Madly they bit into the organs, devoured the gobbets of flesh hanging off the bones, and washed all down with tankards of blood. His eyelids flew open and the drad sprites dispersed. ‘I will not leave thee,’ voweth he, as his weak legs shudder beneath his stupendous weight. At last a paling beginneth to bleach out the night’s inkiness. The reddish glare fadeth. The leaping sprites with their smacking lips and wicked cackles, cracking bones with their teeth, have melted back into the earth. His Highness staggered into the tower room where he collapsed upon a bedding of straw. He passed at once into insensate sleep as if drugged on laudanum, like a great heap of something dead. He did not stir as light spilled across the threshold and bled up the wall. In front of the tall mountains floated a pall of smoke, its thin edge a smudgy line bisecting them, the peaks rising above that false horizon like ears of giant cats.

Your message has been sent and will receive a response.

Meanwhile, you can access

By clicking HERE.